Why Cultural Context Matters in Understanding Mental Health Stigma

February 4, 2021 | By Shane Tan, Junior Associate, Global Health Strategies & Christine Hwang, 2020 Fall Intern, Bridge Consulting

As Roge Karma pointed out in Vox, the COVID-19 pandemic has created a “loneliness epidemic,” with social distancing being a key contributor to the “collapse in social contact” with those close to us, which is particularly hard on populations already most vulnerable to isolation, specifically those already struggling with mental health issues.

But while people worldwide struggle with the same mental torment, cultural norms, traditions and beliefs inevitably affect how people deal with their woes. Undoubtedly, these cultural differences also shape societies’ attitudes surrounding mental health. For example, a comparative study on stigma found that individuals of Asian origin had greater levels of depression stigma as compared with individuals of European origin — the belief that depression brings shame to one’s family was cited as a large contributing factor. Yet another study found that young men in individualistic societies such as the US or the UK are more likely to report feeling lonely than older women in collectivist societies such as China or Brazil. It is important to consider the different cultural contexts that contribute to mental health stigma, so governments and NGOs can promote effective local advocacy campaigns and increase help-seeking amid this global crisis.

Between the two authors of this article, we have lived in the U.S., China, and Singapore — three countries that each lie on varying ends of the individualist vs. collectivist spectrum, which made us wonder: How does mental health stigma differ across East-West differences and in each of these different country’s contexts, and what can we learn from their evolving mental health conversations?

The United States and Inequity in Mental Health Resources

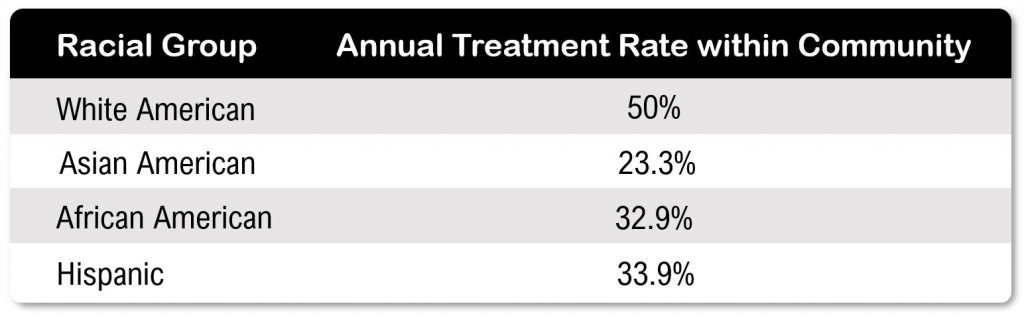

Nearly one in five US adults live with mental illness, and more than half of them do not seek help. Mental health stigma, a key factor in not seeking treatment, varies across different cultural communities, and the socio-cultural influences on attitude toward mental health, among other factors, is reflected in the varying treatment rates within different ethnic communities in the US (Figure 1).

While access to resources and mistrust of the healthcare system among minority groups are issues that may explain part of these statistics, misconceptions about mental illness and taboo around related conversations are decisive factors that hinder help-seeking. To address mental health stigma within communities, many organizations in the US aim to increase education on and accessibility to mental health resources.

Public education. The National Alliance on Mental Illness provides abundant educational resources and key support groups around various mental illnesses, while organizations like Active Minds focus on destigmatizing the mental health conversation among college students.

Increased accessibility. Additionally, availability of mental health support helps with stigma reduction. According to the United Health Foundation, there are a promising 268.6 mental health providers per 100,000 population.

Stigma reduction efforts in the US have become much more a campaign around equity and catering to needs of various local diverse populations, compared to education directed to a broad population to raise awareness for mental health and mental illness, which may be more common in Eastern contexts.

China and the Fear of “Losing Face”

The situation in China is different, but it has some issues similar to the ones in the US. Most people struggling with mental health issues in China also tend not to seek treatment, though at a much larger scale. China CDC’s Center for Mental Health director claimed that for patients with lifetime mental health disorders, only roughly 15 % of them end up seeking counseling. Many patients may only seek a hospital appointment after physical symptoms such as headaches occur, and even then, many will choose to see a general physician rather than a psychiatrist. Studies on Chinese perceptions towards individuals struggling with mental health issues have shown that stigma is a huge factor in low treatment rates.

Public’s misconception. A 2016 study showed that the general Chinese consensus towards mental illness was association with having “weird behavior” and being “harmful to the individual and the society.” The predominant feeling toward patients with mental illness was sympathy and pity, though discrimination, understanding, and rejection were also expressed. A common misconception, as found in 2016 by one of China’s leading online counseling platforms, is the notion that people with mental health issues are weak. Those with depression may be viewed as too “sensitive” or “dramatic,” with misunderstanding surrounding mental health needs prevalent, especially across different generations.

Family pressure. In China, the importance of family and the concept of “face” (one’s reputation) may strongly discourage someone from disclosing their mental health status. Chinese family members often use secrecy or withdrawal to respond to stigma around mental health issues. According to surveyed participants, the main consequences of having a mental illness include individual emotional pain, family burden, and failure in life and career.

However, things are changing, and the conversation around mental health in China today is now as active as ever. The COVID-19 pandemic has provided extra momentum in pushing this conversation forward.

Increased accessibility. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, China saw a surge in the establishment and use of local psychological counseling hotlines amid the pandemic, with schools having expanded mental health counseling, and digital health platforms having stepped up their provision of mental health resources.

Government action. The most recent policy on depression prevention and treatment, passed in September 2020 under the larger framework of the Health China Action Plan (2019-2030), highlighted the goal of achieving depression awareness among 80% of the general population by 2022. This pragmatic, science-based approach seems more acceptable to Chinese people, compared to general wellness tips found in online spaces in the US, given the difference in baseline acceptance of mental health issues.

Media engagement A Chinese-made short film titled Acceptance, rallying to fight mental health stigma and discrimination, had earned considerable media attention during 2020’s World Mental Health Day in China. The film was produced by Haoxinqing, one of the first internet hospitals in China that focuses on psychiatry and counseling, and it was disseminated through multiple media outlets.

Social media resources During World Mental Health Day 2020 in China, various health platforms and media outlets such as People’s Daily Health App and JD Health introduced a series of livestreams from mental health professionals and homepage resources to promote mental health awareness. With more than 2.8 million followers on the Chinese social media channel WeChat, KnowYourself promotes awareness of mental health geared towards young people, publishing articles that draw from academic psychology, pop-psychology, social science, and pop culture, while also offering resources for assessments and therapy.

For China, ensuring adequate mental health coverage remains a significant piece to address for mental health for all — there are a mere 8.75 mental health workers per 100,000 population in China, according to a 2017 WHO report. Yet beyond standardized training of mental health professionals and expanded investment in mental health resources, combating stigma and increasing awareness of mental health has to occur first, through messages that resonate with the Chinese population.

Singapore and Mental Health Stigma in Multicultural Contexts

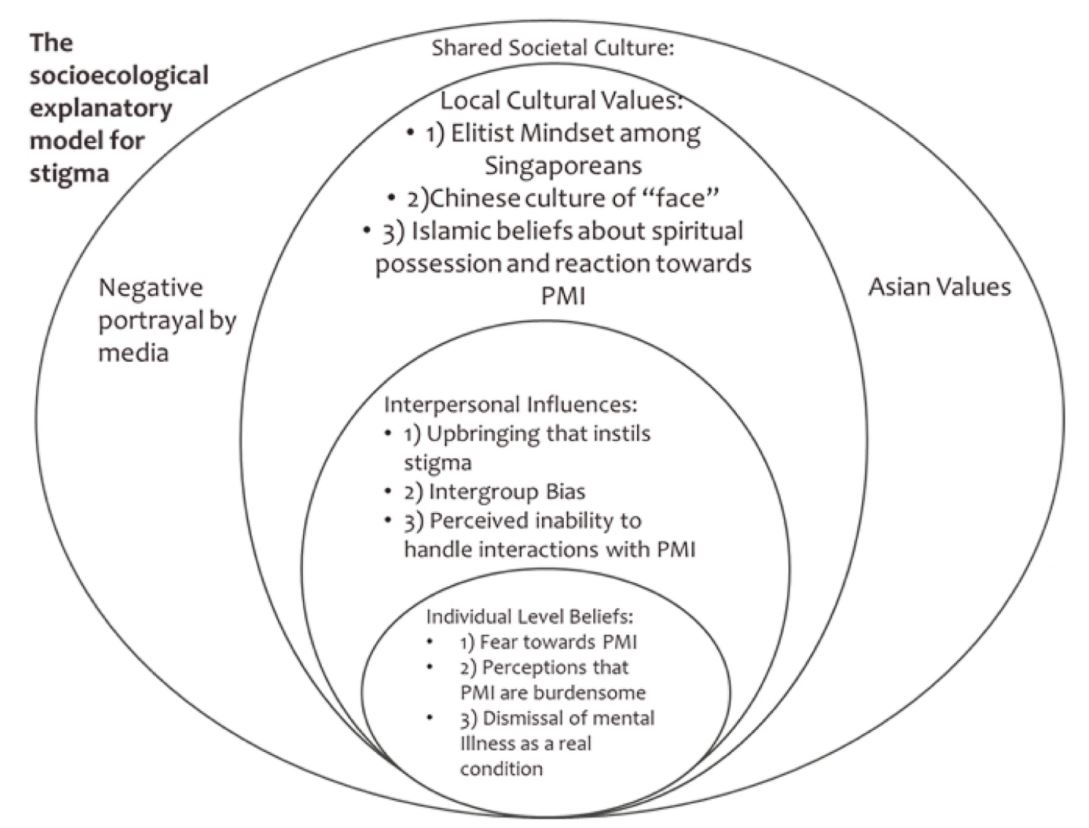

Singapore is a multi-ethnic country, comprising of three main ethnic groups: Chinese (74.2%), Malay (13.4%) and Indian (9.2%), while 3.2% belong to other ethnic groups. While one in seven Singaporeans experience mental health disorders in their lifetimes, the majority (78.4%) of those with mental health conditions do not seek any form of help or treatment, and for those who do, there is a significant delay in seeking treatment.

As studies show, considerable stigma exists towards people with mental illness in Singapore, which discourages them from speaking up and seeking help. A study by Singapore’s Institute of Mental Health echoes this — about half of the study’s respondents said they would be embarrassed if they were diagnosed with a mental illness; nearly a quarter said they would not want others to know if they had a mentally ill relative; and around a third said their friends would see them as weak if they had a mental illness.

Domestically, each cultural community has its individual stigma towards mental health, and this stigma is often associated with the ethnic groups’ traditional beliefs.

Singaporean Chinese. Among Singaporean Chinese, the concept of “face” is also central behind understanding the stigma towards mental illness. Ethnic Chinese cultures tend to place high value in honor and pride. In such a society where the collective family is more important than the individual, anomalies such as mental illness can be stigmatized for a “loss of face,” bringing shame to the family.

Singaporean Indians. Cultural beliefs of mental illness among Singaporean Indians have roots in traditional Indian beliefs about religion and the supernatural. A study in South India found that stigma was associated only with the belief that mental illnesses are caused by karma and evil spirits.

Singaporean Malays. Likewise, mental health stigma among Singaporean Malays has roots in traditional Malay Muslim beliefs. A study in Malaysia found that Muslims are susceptible to the misperception that mental illness is derived from “supernatural activities,” which affirms another study which found that Malay Muslims are likely to attribute the cause of psychiatric illness to fate and religion.

In additional to stigma that discourages many Singaporeans from seeking mental health support, there is also a lack of available mental health support. Singapore has one of the lowest rates of mental health professionals among similar high-income nations, with an average of 4.4 psychiatrists and 8.3 psychologists for every 100,000 people, while that rate in most OECD countries is 15 psychiatrists per 100,000. However, there is a growing awareness among the Singaporean public about mental health which has lessened stigma. More actions have been taken to address this issue.

Increased accessibility. Although the Singaporean government was initially criticized by mental health practitioners for its slow action and removal of psychological treatment from the list of essential services early in the pandemic, the government recategorized mental health services, including private counselling and social work, as essential services during their “circuit breaker” lockdown. This move shows that the government understands the impact this pandemic has on mental health, and the importance of putting measures in place to mitigate that impact.

Media engagement. More and more people are speaking out about their struggles with mental health and their recovery stories, in the media and on platforms such as the Stayprepared.sg site, a mental health initiative by Temasek Foundation.

Our Takeaway

Countries like the US, China and Singapore exhibit the varied causes and effects of cultural stigma towards mental health, which is crucial to acknowledge as we address the widespread mental health consequences of this pandemic worldwide. While different levels of shame and family involvement in mental health conversations exist between the East and the West, there are also distinct attitudes toward mental health within a region’s different ethnicities or cultural groups.

Thus, we need to ask ourselves, our leaders, mental health professionals, and other organizations committed to improving global mental health: How do we spread tailored, culturally appropriate conversations around mental health? A lot more international effort is needed, but global mental health for all has never been a far-fetched goal. Breaking down stigma in different cultural contexts through international collaboration and proper utilization of local resources needs to be an ongoing process.

About the Authors

Shane Tan

Shane Tan is a Junior Associate at Global Health Strategies, a sister company of Bridge Consulting. Prior to GHS, Shane worked as a Copywriter and Community Manager, a Research Assistant to a novelist, and had internships at Salon.com, ELLE Magazine, Surface Magazine, Esquire Singapore Magazine, and Group SJR. Their writing has been published in Yahoo! News, Salon.com, Esquire Singapore, Marie France Asia, Robb Report Magazine, and The Culture Trip. Find Shane on Twitter at @itsShaneTan.

Christine (Yi Ting) Hwang

Christine Hwang is an aspiring global educator majoring in Human Development & Psychology at Northwestern University. She is passionate about social equity, and completed a Fall internship with Bridge Consulting in 2020. Check out her earlier pieces and follow her on Medium here.