A Pandemic, Policy Shifts, Platforms Online: Where is China’s Gender Conversation?

March 8, 2021 | By Marisa Lim, 2021 Spring Intern, Bridge Consulting

25 years – that is how much the COVID-19 pandemic might regress the status of women by, according to global data from UN Women. An increasing number of women around the world are being forced into poverty amid the COVID-19 pandemic, revealing and exacerbating the discrimination women already face. In her latest 2021 Annual Letter, Melinda Gates similarly emphasized the negative impacts of COVID-19 on women especially in developing countries, shedding light on the global economic “she-cession” and increasing unpaid care work. In light of the growing issues confronting women amid the pandemic, this year’s theme for International Women’s Day is Women in leadership: Achieving an equal future in a COVID-19 world.

In China, gender issues have always been a double-edged sword. On one hand, the government has implemented various policies to safeguard women’s rights, which has indeed had a tremendous impact on the progress of women in China. On the other hand, underlying issues continue to plague women throughout China, stemming from a slow shift in the public’s perception of women. The gender conversation in China plays a key role in capturing these problems and changes, and in recent years, the conversation has been evolving with the rise of social media.

Like many other parts of the world, COVID-19 has impacted women in China disproportionately in many ways, with female frontline workers and women at home facing growing challenges in their daily lives. In turn, conversations on gender have pivoted as well, and these changes might be China’s shot at achieving a more equal post-pandemic future.

China’s Progress in Gender Equality

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, gender equality has been a significant part of policymaking in China. While discrimination against females was very prevalent in the early 20th century, gender equality elements of China’s communism ignited a reformative movement for women in China. As a result, significant progress has been made in closing the gender gap for girls and women in access to basic needs.

Politics. In 2018, the proportions of women in government positions in China were the highest in history, accounting for about 24.9% of the total members of the National People’s Congress, starting at 12% in 1954. At the grassroots level, the proportion of women in resident committees was 50.4%.

Health. Maternal mortality ratio has dropped from 80 per 100,000 live births in 1991 to 18.3 per 100,000 live births in 2018. Cervical and breast cancer checkup has covered all poverty counties across China as of 2018, with a 75.5% screening rate.

Education. The gender gap in compulsory education has essentially been eliminated, with female literacy rates having gone up to 95.16% in 2021, from 51.14% in 1982.

Economy. China has one of Asia-Pacific’s highest labor force participation rates for women, but the numbers have been declining from 73.2% in 1990 to 60.5% in 2019. While women only made up 9.7% of board directors in 2019, Chinese women make up 57% of the total number of self-made female billionaires in the world.

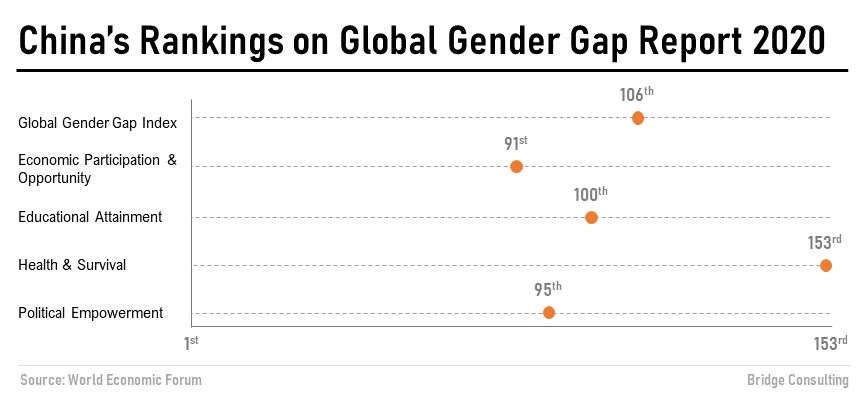

But stopping here is not enough. China still has a long way to go in achieving gender equality, having been ranked a mere 106th out of 153 in the latest World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Index. And the Chinese public are starting to voice out their opinions on the gender issues that China has yet to address.

The Gender Conversation in China Today

With the rise of social media and more channels for online public discussion in China, the gender conversation in China has become more vocal in recent years. Much discussion revolves around unresolved gender issues in China, which are the consequence of a slow cultural paradigm shift in the population despite progressive gender policies. While the one-child policy, for instance, was aimed at population control, the Chinese preference for sons had resulted in high female infanticide rates for years. Today, these gender issues are still prevalent in other aspects.

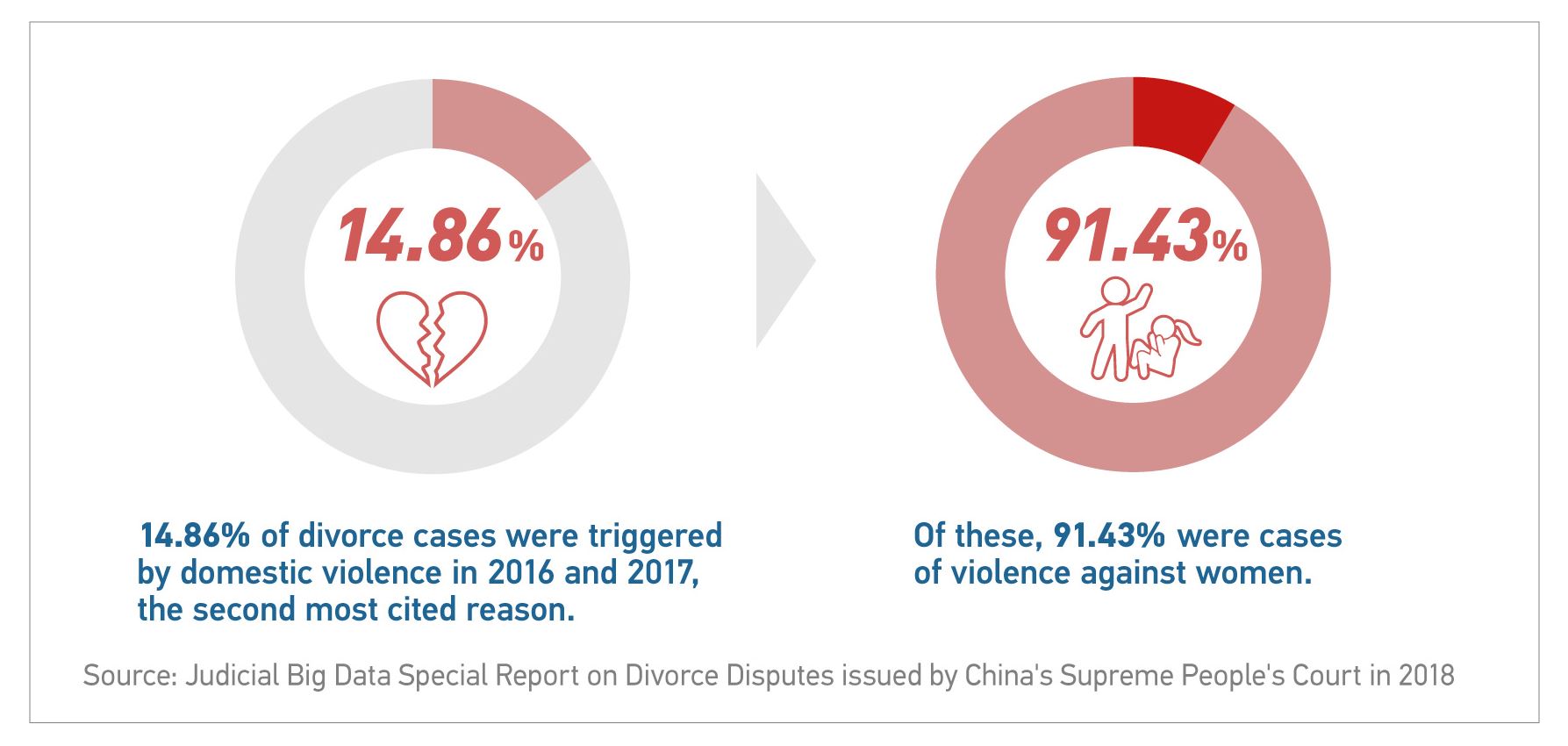

Domestic violence. In 2016 and 2017, domestic violence was the second most cited reason for divorce cases in China, and of these, 91.43% were cases of violence against women. Despite the prevalence of domestic violence, China implemented a 30-day divorce cooling-off period to lower divorce rates, which received huge backlash from the public who saw it as a discriminatory action against women suffering from domestic violence.

Body image anxieties. Nearly 60% of respondents have body image issues, a recent by xiaomei.com on Chinese undergraduates showed. The rise of viral body image trends on social media in recent years has only worsened the body image crisis for Chinese women. While female undergraduates worry how their appearance might affect job prospects, older women face anxieties about childbirth and pregnancy. However, conversations on women’s body image have always been rather quiet.

These gender issues have been prevalent for many years in China, but they are only beginning to surface now, through discussions on various online platforms. Social media has undoubtedly shifted the gender conversation in China in recent years. But how has COVID-19 impacted these conversations in the past year?

COVID-19’s Impact on Women in China

To understand COVID-19’s impact on the gender conversation in China, we must first look at the issues that have plagued women in China during the pandemic. Around the world, COVID-19 has not only revealed, but also worsened gender issues that have yet to be resolved. In China, a large fraction of women that struggled during the pandemic consisted of female frontline workers; during the initial outbreak, women made up two-thirds of the medical volunteers and more than 90% of the nurses in Hubei. Lockdowns have also exacerbated the problems confronting women staying at home for prolonged periods of time. These rising issues will give a better insight into the changes that COVID-19 has brought to the gender conversation in China.

I. Impact on Female Frontline Workers

A central topic in the gender conversation in China over the past year has been women in the healthcare sector, especially female frontline workers. Their efforts were far from unnoticed. That said, these women were confronted with more challenges than their male counterparts on the job; many of their needs were neglected and efforts diminished by the media.

Job challenges. Some female frontline workers had to shave their heads or cut their hair to don ill-fitting equipment that were designed for men, and to avoid infections as advised by experts. Others had limited access to menstrual products, with some reportedly given birth control pills to delay their menstrual cycles. Though hailed as noble sacrifices by the media, the necessity of these actions was questioned by many online.

Mental trauma. Unbalanced and underdeveloped healthcare systems, alongside underappreciation of nursing staff, have taken a toll on the mental health of many female frontline workers. Check out our previous publication on the mental health challenges faced by frontline workers in China.

Media misrepresentation. Televised dramatizations focusing largely on male hero narratives amid the pandemic control in Wuhan sparked fierce debates online on gender discrimination in the media industry. There has also been online outrage against news reports leaving out significant female doctors who had also sounded the alarm when COVID-19 was first detected in Wuhan.

Despite numerous praises for female frontline workers in state media, discussions on social media have helped shed light on the unaddressed problems that this group of women had to quietly put up with. Can the same be said about the problems COVID-19 has caused for other women in China?

II. Impact on Women in China

The new normal introduced by the pandemic situation has also created new challenges for women throughout China. With more families at home due to lockdowns and closed schools and offices, women have been at a greater risk of worsening domestic issues.

Household burdens. With schools closed, Chinese mothers are also facing increased household duties alongside working from home. A recent case of a Chinese husband having to pay his wife for the housework she had done during their five-year marriage reminded the public of the household burdens that most women face, unlike men.

Increased violence. Despite the lack of recent statistical reports on intimate partner violence in China, reports have similarly shown a surge in violence against women during the pandemic lockdown across China. Research has shown that 90% of the causes of violence are related to COVID-19.

The problems that COVID-19 has brought about for women are far from few. These issues are merely an extension of previously unresolved systemic discrimination against women in China. But the pandemic has also seen a growing population of active social media users, with more people having to interact online, rather than face-to-face. What does this mean for the post-pandemic gender conversation in China?

Post-Pandemic Progress in China’s Gender Conversation

Growing discussions on gender in China amid the pandemic situation is a promising sign for the country, and could play a vital role in its COVID-19 response. Having shed light on the problems confronting women during the COVID-19 crisis, how might these conversations on gender pivot post-pandemic?

More open conversations. The pandemic has seen more fervent discussions about previously dormant gender issues online. While conversations on body image issues have always been rather quiet pre-pandemic, open conversations on physical appearances and menstrual hygiene have grown, following the issues confronting female frontline workers during the initial outbreak.

Stronger public opinions. Besides increased discussions, the pandemic has also seen netizens voicing out their opinions against gender discrimination on social media platforms. Following a lack of female representation in dramatizations of the pandemic response in China, many netizens have voiced out their dissatisfaction with the diminished media coverage on female frontline workers.

Women-led response. Young women across China are leading pandemic responses, following increased discussions on the women’s issues during the pandemic. Liang Yu, a young female blogger from Shanghai, initiated a female sanitary hygiene donation drive for frontline workers in need, and is planning to extend the help to girls in poverty in China. In Wuhan, a women-led campaign has increased public awareness on domestic violence against women and supported victims through safe, open conversations.

While the pandemic has brought about more problems for women in China, it has also undoubtedly pivoted the gender conversation in the right direction. Awareness on gender issues in China is growing, with increased discussions, vocal opinions and initiatives nationwide. Women empowerment could also be useful in China’s COVID-19 response, as proven with successful women-led projects carried out in Shanghai and Wuhan.

This International Women’s Day comes after a year like never before. While the COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect populations worldwide, the epidemic of gender discrimination against women should not be neglected as well. With the progressive gender conversation growing in China amid the pandemic, the country should leverage on this opportunity to tackle existing gender issues and further empower women to be part of the response. Only then can China strive towards an equal future in a COVID-19 world.

About the Author

Marisa Lim

Marisa Lim is a Singapore-based aspiring trailblazer majoring in Biomedical Engineering with a specialization in Robotics, passionate about global health and social causes. Find Marisa on LinkedIn.