Wildlife Trade and COVID-19: Why Can’t China Just Ban It For Good?

June 4, 2021 | By Marisa Lim, 2021 Spring Intern, Bridge Consulting

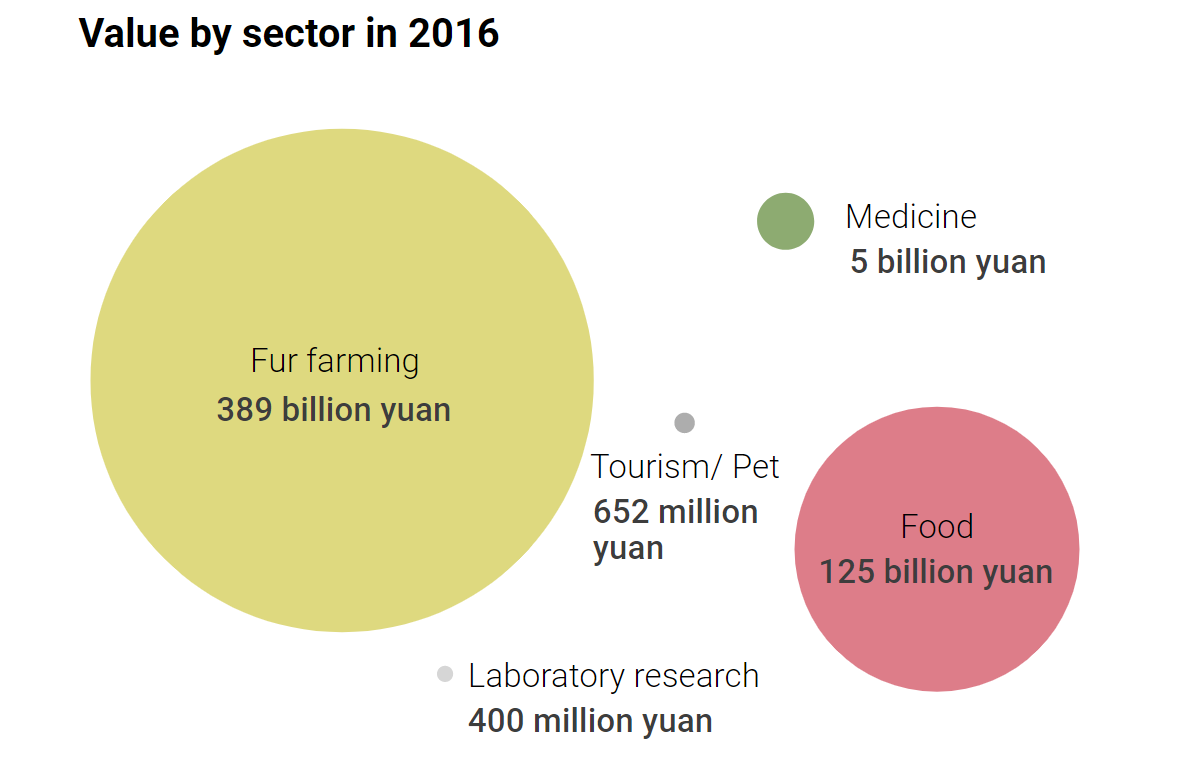

Providing over 14 million jobs, valued at US$74 billion, and putting food on the plate for countless families in rural China – that is the size and significance of the wildlife trade sector in China, according to a report by South China Morning Post in 2016. Out of 14 million jobs, over 250,000 have been affected by China’s epidemic-inspired ban on wild animal consumption, which took effect in January 2020 – and this number excludes the many families that have lost their main source of income from wild animal farming.

The economic and social impact of a blanket ban on wildlife trade in China is undoubtedly devastating, but the vast number of workers in this sector also means that millions of people are constantly in close contact with wild animals in China everyday. Although many of these interactions are closely monitored and controlled, humanity has been constantly reminded of the disastrous consequences a single unmonitored interaction with wild animals can cause – from the 2002 SARS outbreak, to the 2009 H1N1 swine flu, and most recently, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

World Environment Day 2021 calls for urgent action to revive our damaged ecosystems, and a key motivation behind this is the reminder that COVID-19 brings us: the consequences of ecosystem loss can be deadly for humanity. Natural habitat loss has created ideal conditions for zoonotic pathogens, including coronaviruses, to jump the species barrier from animals to humans. The solution to this is recognizing the utmost importance of One Health, a multi-sectorial approach that reiterates the fragile, interdependent relationship between ecological health and human health.

As a country with high human population density and wildlife abundance, China is a “high-risk area” for emerging infectious diseases, according to Martin Raiser, World Bank Country Director for China. The One Health approach is, therefore, highly applicable to China; but unlike the rest of the world, China’s One Health approach must also take into consideration many socio-economic factors, including the many lives uplifted by wildlife trade and the cultural significance of wild animal consumption, among others.

“By shrinking the area of natural habitat for animals, we have created ideal conditions for pathogens – including coronaviruses – to spread. But we can build back better.”

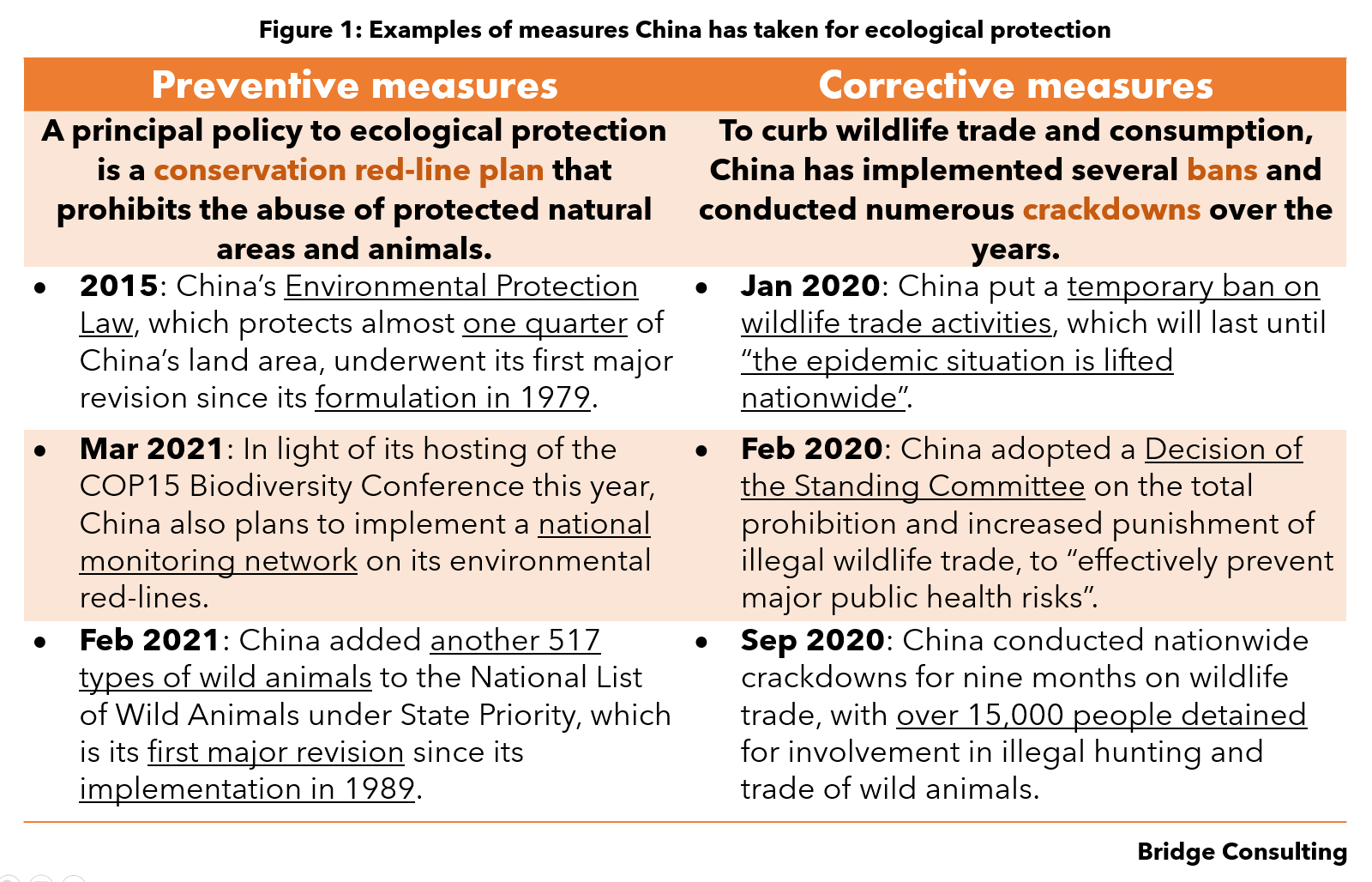

What actions has China taken for ecological protection?

Part of the One Health approach is to first have government action for ecological protection, which includes wildlife and environmental protection. The Chinese government has sought many preventive and corrective measures that protect ecosystems and crackdown on illegal actions respectively (Figure 1).

These actions, however, do not involve multi-sectorial communication, collaboration, and coordination, as the One Health approach suggests. China’s complex wildlife trade landscape has limited the involvement of non-governmental or multilateral organizations in this issue. For instance, the World Health Organization (WHO) and its partners have also called for a worldwide suspension of bushmeat sales and consumption, but with over 14 million livelihoods at stake, this blanket ban is hardly feasible in China. Therefore, understanding the diverse cultural climate in China, with relation to wildlife trade, is an important factor in guaranteeing the success of the involvement of multiple stakeholders in China’s One Health approach.

Understanding the significance of wildlife trade in China

Evidently, majority of China’s actions for ecological protection thus far have been targeted at wild animal trade and consumption. Unlike the threats of recreation or trophy hunting to wildlife conservation in North America and Europe, China’s biggest threat is its wildlife trade industry. However, the interdependent relationship between humans and wildlife in China is a fragile and complex one.

Over many years, the wildlife trade industry has elevated many lives out of poverty. In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping spoke of “targeted poverty alleviation”, which entails the tailoring of poverty alleviation efforts to the individual situations of each village in China. In line with this, to meet poverty reduction targets, several local authorities encouraged the growth of the local “wildlife breeding and domestication” industry. As a result, a multitude of wild animals, including bamboo rats, pangolins and civets, were legally bred in huge numbers. This has created a diverse cultural landscape of whole populations in rural regions in China being heavily reliant on wild animal farming, trade and consumption for sustenance.

Wild animal farming for food. Valued at over US$19 billion in 2016, the food sector for wild animals has been an important source of income for many families in rural China, especially those that have turned to bamboo rat farming. The Huanong Brothers (华农兄弟 huánóng xiōngdì), two bamboo rat farmer-influencers from Jiangxi province with over 6 million followers on video-streaming site Bilibili (view their YouTube channel here), are just one of many families affected by China’s ban on wild animal consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic. Documenting the devastating impact of the ban on their bamboo rat farm, many netizens on Weibo even sympathized with the Huanong Brothers.

Mink fur farming. As the largest sector in the wildlife trade industry, the fur farming sector was valued at over US$60 billion and supported roughly 7.6 million jobs in 2016. In 2018 alone, 20.7 million mink pelts were sold produced in China. While wild animal farms for food consumption were completely shut down during the pandemic, little action was taken on its mink farms. Most recently, Chinese suppliers are taking advantage of a surge in global prices for mink fur after millions of mink were culled in Denmark and Europe, the world’s top supplier of mink fur.

Use in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). 11 animal species are still being bred for use in TCM, including the Asian black bear, different species of deer and pangolins. Under the Wildlife Protection Law, China still permits the legal trade of pangolin scales, leopard bone and captive-bred tiger skins for non-food purposes, including TCM. TCM still has a huge cultural significance in China today, with a history dating back to the second century BC, even though scientific evidence for the medicinal value of such treatments remains debatable. Valued at US$780 million in 2016, the TCM industry also is growing its exports through the Belt and Road Initiative, which will increase the demand for such wildlife.

China’s One Health approach: Bringing together international and local organizations

While China’s own ecological protection actions have been far from few, its diverse cultural climate has presented many stakeholders in this issue, including the multiple sectors that make up the US$74 billion wildlife trade industry in China. As such, China’s unique One Health approach balances the conflict between the livelihoods supported by this industry and the need for ecological protection to protect its public health. This unique approach has involved several international organizations that have successfully worked with local organizations and navigated the local wildlife trade landscape.

Improving disease monitoring and control measures in local agriculture industries. In 2020, the World Bank launched the Emerging Infectious Diseases Prevention, Preparedness and Response Project for China, a project that will pilot a multi-sectorial One Health approach to reducing the risk of zoonotic and other emerging health threats in Jiangxi and Hainan provinces, where agriculture is an economy driver. While still in progress till 2025, this project aims to find a common ground between legalized animal and wildlife trade, especially regarding China’s wet markets, while guaranteeing proper measures to monitor and control diseases.

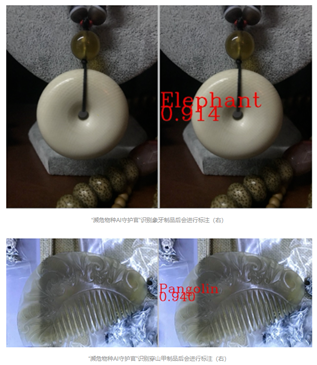

Providing expertise to Chinese stakeholders to improve law enforcement. In April 2020, the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) and Chinese search engine Baidu launched a deep learning tool called AI Guardian of Endangered Species (濒危物种AI守护官), which will identify images of endangered wildlife products traded on e-commerce platforms in China, and traced back to the source links for removal of illegal wildlife trading sites. IFAW has also worked with logistic companies and local governments in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region to crackdown on wildlife trafficking networks across critical land borders in the area.

Establishing eco-friendly livelihood opportunities with local authorities. The Nature Conservancy (TNC) has been working with local authorities, local conservation groups and scientific research institutions to support wildlife and ecological conservation projects in China for almost two decades. In its two key projects to establish the Yunnan Golden Monkey Protection Network and Laohegou Land Trust Reserve, TNC and its local partners have committed themselves to help communities living in these biodiversity-rich areas to profit from forest-friendly livelihoods to take the place of poaching and logging. In the latter project, TNC and the Paradise Foundation International established a community development fund to help over 60 families double their income through eco-friendly agriculture.

Organizing awareness campaigns with Chinese KOLs. On World Wildlife Day 2017, United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), IFW and TNC launched the “Protect Our Wildlife Star” (守护地球的明星) campaign with several Chinese celebrities as advocates, raising awareness on wildlife conservation among China’s younger demographic. With the help of these celebrities’ influence, the campaign’s Weibo hashtag (#守护地球的明星) garnered over 97 million reads and 700,000 discussions. Other successful campaigns with local celebrities include IFAW’s “Mom, I Have Teeth” (“妈妈,我长牙了”) campaign and WWF’s joint campaign with China Customs and the Forestry Administration featuring popular Chinese actor Huang Xuan.

Takeaways

China’s One Health approach is unlike any other countries’, as it must take into account the complex relationship and conflict between its wildlife trade industry and ecological protection. Given its diverse cultural climate, it is vital for foreign organizations to have an informed understanding of the country’s One Health approach to effectively tackle the deep-rooted conflict between wildlife trade and ecological protection. However, while China and international organizations have been successful in the implementation of measures against some forms of wildlife trade, there is still much left to be done. A complete ban on wildlife trade in China does not appear to be an effective long-term solution at this stage, but stringent regulation and monitoring in this industry are possible compromises to prevent future public health risks.

Read more from the links in Figure 1:

- 2015: China’s Environmental Protection Law, which protects almost one quarter of China’s land area, underwent its first major revision since its formulation in 1979,

- Mar 2021: In light of its hosting of the COP15 Biodiversity Conference this year, China also plans to implement a national monitoring network on its environmental red-lines.

About The Author

Marisa Lim

Marisa Lim is a Singapore-based aspiring trailblazer majoring in Biomedical Engineering with a specialization in Robotics, passionate about global health and social causes. Find Marisa on LinkedIn.