September 4, 2020 | By Angel Teh, Associate Director, Bridge Consulting

2019 was the worst year on record for dengue — a viral infection transmitted by the Aedes mosquito, which also spreads Zika and yellow fever. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), every region worldwide was affected, with some countries hit for the first time. Efforts were stepped up and plans were rolled out in response. Yet, as we commemorate World Mosquito Day this year, we are seeing increases in dengue cases across several countries, and in some, record high numbers. Perhaps ironically, prevention efforts against COVID-19 have had a major hand in this surge.

More than 25,000 cases of dengue have been recorded in Singapore this year, making this the worst outbreak the country has ever seen in a single year, let alone within an eight-month period. Among the factors Singapore’s National Environment Agency (NEA) has identified behind the surge is the stay-home measure enacted to slow the spread of COVID-19. As the Aedes mosquito bites during the day, more people staying home where mosquito populations are high have meant greater likelihoods of getting bitten — in other words, greater risks for spreading dengue.

Singapore is far from the only country in this predicament. Several others including Malaysia, Indonesia, Brazil are similarly seeing dengue outbreaks unfolding in tandem with COVID-19. Brazil, for instance, has now seen over 3.4 million COVID-19 infections, alongside at least 1.2 million dengue cases, according to the Pan American Health Organization. Unfortunately, dengue cases stand to rise even further with the start of seasonal rains across several Latin American and Asian countries over the past month through to November.

COVID-19 Hampering Dengue Prevention and Research

Preventative measures aimed at destroying mosquito-breeding sites remain among the best ways to curb dengue’s spread to date. But lockdowns and other restrictions have meant cutbacks on many of such efforts. In Pakistan, plans to disinfect shops and markets that had dengue outbreaks in 2019 had to be halted as funds were redirected to COVID-19 efforts.

It has also become too difficult to enroll patients for research with the social-distancing measures, said Scott O’Neill, founder and director of the World Mosquito Program, in reference to dengue research at the WMP Tahija Foundation Research Laboratory in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. The facility has been converted for use as a COVID-19 testing site. Similarly, India’s National Institute of Malaria Research in New Delhi has had to halt all field work as its center is now used for validating COVID-19 testing kits.

No Antivirals or Vaccines Yet?

COVID-19 notwithstanding, dengue cases have increased over 30-fold in the last five decades, and according to the WHO, about half of the world’s population is now at risk. Increased temperatures and humidity brought on by climate change have also enhanced conditions for mosquito breeding. This is further compounded by the rapid urbanization occurring in many dengue-endemic nations, which means even greater numbers are living in closer contact with disease-carrying mosquitoes.

Yet, there remains no effective antiviral therapy or vaccine approved for dengue to date. Dengvaxia, the world’s only approved vaccine, became commercially available in 2016 after 20 years of research by French pharmaceutical company Sanofi Pasteur, but is exclusively recommended to those who have previously had dengue fever. Regrettably, the recommendation was made only after evidence of an increased risk of severe dengue in those who had not previously been infected emerged — including the deaths of children in the Philippines from alleged vaccine complications following a school-based program.

That dengue comes in four variations (serotypes) has served to complicate research efforts. Exposed to one, a person is assumed to be immune to it for life. However, a subsequent infection with another dengue serotype can cause a deadly hemorrhagic shock in the victim. This unusual twist in the disease has hindered vaccine development for years, though data from clinical trials of other dengue vaccines currently in the pipeline show promise. For the same reason, antiviral research for dengue has also faced an uphill battle.

Stopping the Buzz: So What’s Being Done?

Given the absence of an effective vaccine and drug to cure, mosquito control remains the only method currently available to reduce disease risk. A number of such control methods exist, including insecticide spraying and genetic modification. Most recently, however, global attention has been on methods involving Wolbachia, a naturally-occurring Zika and dengue resistant bacterium, pioneered in 2011 by scientists at Monash University in Australia. Two key Wolbachia-based approaches in particular have gained momentum:

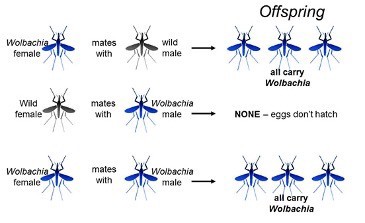

1. Release both male and female Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes into the environment

As Wolbachia is only passed from females to their offspring, releasing females with this bacterium means that it will gradually be passed throughout the mosquito population, making them resistant to Zika and dengue. Also known as the World Mosquito Program’s Wolbachia method, more than ten countries including Australia, Brazil, Colombia, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and India, have signed up.

2. Release only male Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes

A second approach taken in Singapore and China is aimed at quelling the population of mosquitoes by releasing only male Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes, which do not bite humans, and importantly, are unable to fertilise the eggs of non-infected females. This approach is more costly as it involves sorting the gender of mosquitoes and requires sustained release of mosquitoes — at least until the population crashes. Nonetheless, following successful trials, both Singapore and China have set up facilities to produce millions Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes a week each.

Addressing Risks and Raising Awareness In the Meantime

In addition to the factors of availability and cost discussed above, as past controversies have made abundantly clear, public acceptance also play a critical role. Beyond the Dengvaxia vaccine controversy in the Philippines mentioned above, earlier examples include the collapse of trials with sterilised mosquitoes in India in the 1970s following accusations from politicians of biowarfare, as well as eventual revelations of DDT’s adverse environmental effects and potential human health risks. While independent risk analyses indicate that the release of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes poses negligible risk to humans and the environment, much room for public education to address the significant health and safety concerns about bioengineered mosquitoes remain.

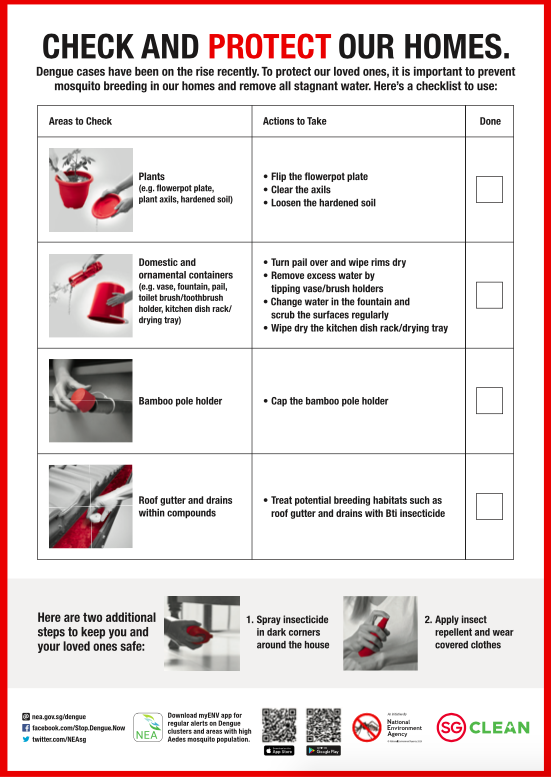

Meanwhile, public actions also have a vital role to play in the control of mosquito-borne diseases like dengue, especially as the mosquitoes in question breed in stagnant water often found in homes. The poster below from Singapore’s National Environment Agency for example provides a checklist highlighting the direct link between sanitation and protecting against dengue, alongside precise steps residents should take.

2020 has certainly thrown a spanner in the works across dengue-related initiatives globally. But as we await the successes of both ongoing and future scientific endeavors, let’s be sure to play our part in the little ways we can.

About The Author

Angel Teh

A Beijing-based global health and development enthusiast. Find Angel on LinkedIn.