Reflections from the 2020 China Census: Growing Cities, Ballooning Pollution

August 4, 2021 | By Christine Ow, 2021 Summer Intern; Boyang Mao, Associate Director, Bridge Consulting

In the second piece of our “Reflections from the 2020 China Census” series, we will be looking at China’s growing urban population. The growth of China’s cities is not a new phenomenon, in fact, it is a trend that has persisted for decades since China opened its economy in the 1980s. While this has yielded many economic benefits for the country, one has to ask, at what cost did this growth come at? One answer to this question is the environment, specifically air pollution. In this article, we will be taking a closer look at China’s air pollution problem as a result of rapid urbanization, the policies that have been implemented to combat them, and future steps the country should take to face this looming problem.

China and Urbanization

From the 2020 Census. According to the population census released in May 2021, China’s urban population has continued to grow, especially in the more developed coastal cities in the East. Specifically, since 2010, the urban population has grown by 236.42 million people, which is equivalent to an increase of 14.21 percent.

Historical Trends. Urbanization in China has been going on for several decades now. Starting in the 1980s, following the loosening of the resident registration system (Hukou System 户籍), and the opening of the economy, China has gradually seen a population shift eastward where many of the new factories and industries were being built up. Motivated by higher-paying jobs, and an escape from village life, young people flocked to the coastal cities. However, in recent years, an interesting phenomenon has developed in China. In part caused by the high cost of living and development of the digital economy, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, the country is now seeing ‘reverse migration’ where migrant workers are leaving the big cities and not returning. While the number of reverse migrants is growing it still doesn’t change the reality that China’s cities are being forced to expand with its swelling population.

Urbanization’s Impact on Air Pollution

Emissions from construction. As the urban population grows, so must the cities to provide for the needs of their new residents. By one estimate, every year, China builds about two billion square meters of new floorspace. This much construction inadvertently leads to immense carbon emissions, both from the process of building new infrastructure and from the production of necessary materials like cement and steel. According to one study of China’s building activity in 2015 – a relatively low year of construction – it alone accounted for around 18% of reported carbon emissions in the country.

Emissions from urban consumption. New urban residents also directly contribute to emissions through a change in their consumption patterns. It should come as no surprise that on average, city dwellers take part in more emission-intensive activities than their rural counterparts. Put into numbers, in China, urban dwellers emit around 1.4 times more carbon dioxide than rural residents. This comes from transportation and commercial building activity which is more intense in the cities, and the use of fossil fuels like coal for urban heating.

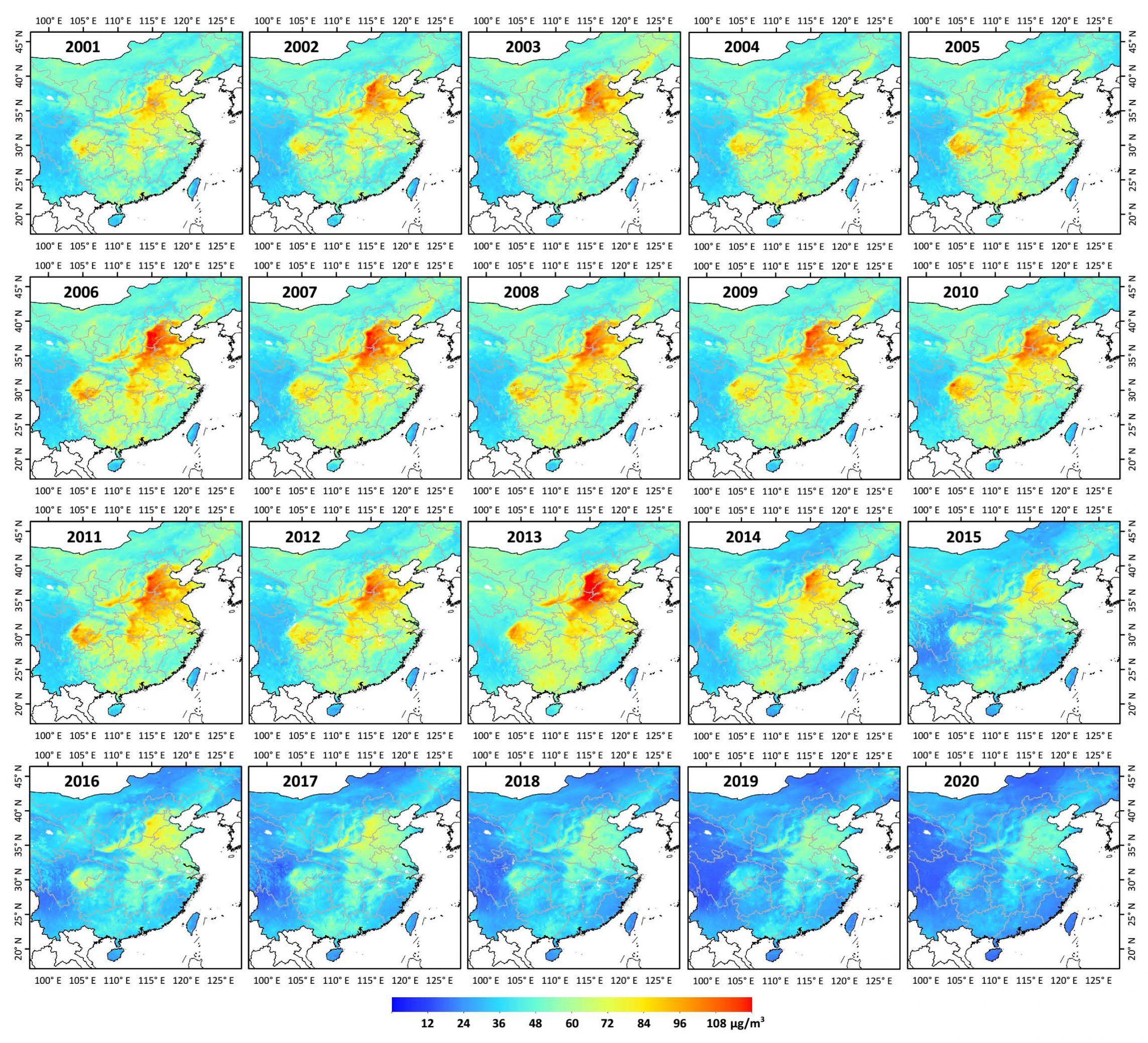

Decrease in air quality. Overall, this contributes to a decrease in urban air quality as seen by a higher concentration of particulate matter (PM2.5). We look at PM2.5 concentrations in particular as it is a result of human activity, and in recent years it is the pollutant that has seen the most distinct proportional increase. Urban centers in China, generally exhibit a higher concentration of PM2.5 than their rural counterparts. This has consequential impacts on the health and wellbeing of China’s city residents, from severe visibility issues to respiratory problems.

China’s Policy Solutions

National legislation and policy. In response to deteriorating atmospheric conditions, as well as rising public concern regarding the environment and related health impacts, the State Council issued national plans for air pollution prevention and control. The Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan (issued in 2013, covering the period of 2013-2017) and the Three-Year Action Plan for Winning the Blue Sky Defense Battle (issued in 2018, covering the period of 2018-2020) sought to articulate the nation’s new air pollution governance. Both of these plans targeted PM2.5 as the major air pollutant. They set air quality improvement goals and outlined macroscopic strategy, measures, and tasks on issues related to industries, energy structure, transportation, pollution monitoring, public participation, etc. Critically, in 2015, the Law of the P.R. China on Air Pollution Prevention and Control was revised, with more stringent requirements, enforcements and penalizations. This revision provided solid legislative support to the implementation of the current action plans.

Local policy implementation: Beijing. It is a common practice that provinces and cities would formulate local level action plans based on the targets and principles of national action plans, and with modification according to local pollution features. In Beijing, the city has nearly no heavy industry, therefore, most of its local air pollution emission is from transportation and residential coal consumption for heating. Therefore, the air pollution control action plans of Beijing focuses on measures regarding automobile emission and cutbacks in coal consumption. This is different from the national action plans which pay more attention to industrial emission.

Coordinated regional air pollution control mechanism. The Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan identified 3 key regions for air pollution control, namely the Northern China Plain Area, Yangtze River Delta, and Pearl River Delta, each region included several provinces and cities. To better align air pollution control measures across administrative divisions, the coordinated regional air pollution control mechanismwas established. The mechanism was led by the State Council and consists of relevant provincial governments in the three regions respectively, as well as related ministries. The coordination mechanism has proven to be effective, especially in terms of unifying measures, joint enforcement, and heavy pollution episodes response.

Future policy. After the accomplishment of the two action plans as described above, China has yet to issue new independent air pollution action plans. Instead, the overall environmental protection, including air pollution prevention and control, will be integrated into the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) for National Economic and Social Development. With this new approach, better coordination between environmental governance and economic development is expected.

Evaluation of Policies

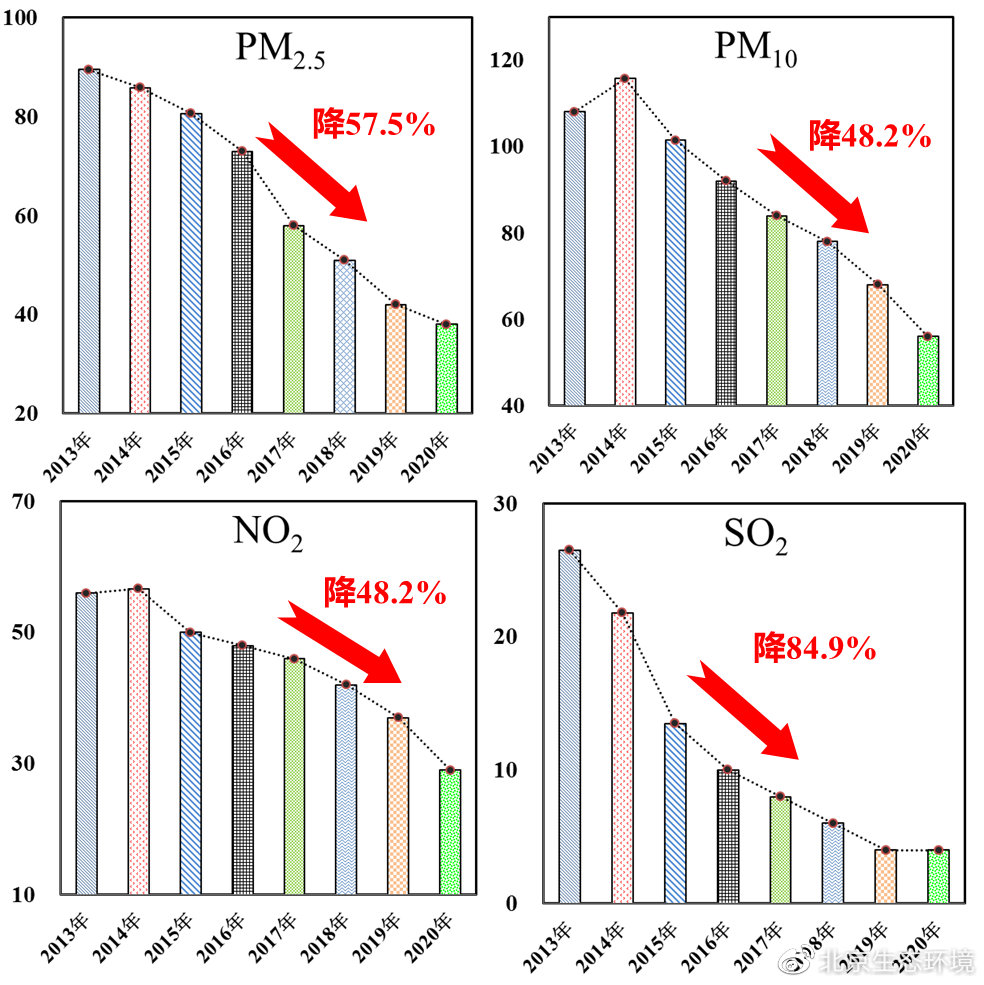

Significant improvement of air quality. With the solid implementation of the air pollution prevention and control action plans, a significant air quality improvement has been achieved. By the end of 2019, the ambient PM2.5 concentration in 76 Chinese cities met the 35µg/m3 national standard. Although there are still 261 cities that have yet to meet the standard, the annual average PM2.5 concentration among all these cities was 40µg/m3. As for the case of Beijing, the annual PM2.5 concentration decreased from 90µg/m3 in 2013 to 38µg/m3 in 2020, which is a 57.5% reduction rate. Meanwhile, the concentration of other major air pollutants is rapidly decreasing trend.

(Image Caption: Annual concentration of PM2.5, PM10, NO2, SO2 in Beijing 2013-2020. Source: Beijing Municipal Ecology and Environment Bureau)

Meeting international standards. Despite the progress China has made in reducing air pollution, like with many things related to climate action, more can be done. For one, while China has been successful in reducing air pollution levels in some cities to meet national standards, these standards are still higher than those set by the World Health Organization (WHO). For PM2.5 specifically, China limits the annual mean at 15µg/m3 for conservation areas, and 35µg/m3 in residential and industrial cities. Both standards are above the WHO’s stipulations which sets the limit at 10µg/m3. To meet international standards, therefore, more aggressive steps will need to be taken.

Balancing economic needs. Traditionally, climate policy has often been at odds with economic needs, and China is not immune to this push-and-pull. The COVID-19 pandemic has created an economic crisis for many countries, and in China’s case, this has led to a resurgence in carbon emissions. While China did see a sharp decrease in emissions early in the pandemic as a result of lockdown measures, coal demand has shot up sharply as the country moves into economic recovery. In the first half of 2021, emissions went up by 9% in contrast to pre-pandemic 2019, and carbon dioxide emissions from the energy sector are predicted to increase by 1.5 billion metric tons, the highest increase since 2010. These trends indicate that China will prioritize economic growth over environmental needs, which raises concerns about its commitment to its long-term emissions reduction goals.

Looking Ahead: Our Recommendations

Policies have been put in place, and the Chinese government has articulated a commitment to tackling air pollution. However, as explained above these policies are not sufficient. What are some things China can do to further combat urban air pollution?

Co-benefits of Climate actions and air pollution actions. Given the fact that most technical solutions for air pollution have been implemented over the last 8 years, further improvement of air quality will require a new driving force. “It would be extremely difficult to make a breakthrough and reduce the PM2.5 concentration to 15µg/m3 and lower, if we cannot integrate air pollution control with carbon reduction and energy structure reformation”, said academic He Kebin. China has made its commitment to carbon neutrality by 2060, however, the nation’s energy structure is still highly dependent on fossil fuel – especially coal. China consumed 4 billion tons of coal in 2019, which accounted for 57.7% of the country’s energy consumption of that year. As the industrial sector is both the largest energy consumer and emitter in China, there is great potential in exploring the co-benefits of air pollution reduction and climate action. The co-benefit in the transportation sector is promising as well, with the increasing use of renewable energy and the growth of the electric vehicle fleet.

Green Urbanization, Sustainable Cities. Urbanization is an inevitable consequence of China’s economic growth, resisting it will be futile, so adapting to it will be key. Internationally there has been growing interest in sustainable urbanization and China is no different. In 2011, the 12th Five-Year Plan for Green Building and Green Eco-city Development selected 100 new areas to develop eco-cities: cities that are purportedly more sustainable and environmentally friendly. Some cities have already been built, among them, a notable one is the Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-City. While it’s still too early to make conclusions on the long-term impacts of these eco-cities, their development presents a hopeful future for China to continue urbanizing while working towards their climate goals.

About the Authors

Christine Ow

Christine Ow is a Singaporean international student currently studying at the University of California, Los Angeles, majoring in Political Science. She is passionate about sustainable development and environmentalism and hopes to work in those fields in the future. Find Christine on LinkedIn.

Boyang Mao

Boyang Mao is the Associate Director at Bridge. He has close to 10 years of experience focusing on sustainability and international affairs, working for various organizations such as the Chinese local government, NGO, and a foreign embassy in China. He is an enthusiast for enhancing SDGs and improving social good through international collaboration.