History and prospects of improving maternal health in an aging China

Chinese mother and child | Source: UNFPA China

August 2, 2022 | By Mia Landeck, 2022 Summer Intern, Bridge Consulting

The reversal of the U.S. Supreme Court case Roe v. Wade, on June 24th 2022, brought the topic of abortion and women’s sexual reproductive health back under the global spotlight. The ruling effectively overturned the constitutional right to an abortion in the United States. Within 24 hours of the court decision, the topic was trending worldwide, including on Chinese social media, with hundreds of millions of views of related hashtags. While many Chinese netizens responded to this event by praising their domestic laws on freedom of abortion for women, discourse on the association between abortion policies concerning China’s ongoing population crisis was also brought up by various groups.

China is currently facing declining birth rates and a rapidly aging population, which is expected to shrink by 2025. These trends pose various socio-economic implications on its demographics and have raised alarming concerns for the government as they try to introduce new policies encouraging families to have more children.

In fact, the government has made significant positive changes towards improving women’s health. China has enjoyed a tremendous improvement in maternal and child health (MCH) over the past few decades, with great reduction in maternal mortality and increased access to health services. However, remaining regional disparities in quality of care and in particular, a legacy of family planning policies that have impacted women’s livelihoods in disproportionate ways are bound to affect further progress. The current challenge that China faces with its population will require new approaches and understandings of what women want and need today.

Chinese mothers and their babies | Source: BBC

Development of maternal and child health policy in China

Over the years, China has made considerable progress in MCH. In 1978, when China launched its reform and opening up policy, maternal and child healthcare began to experience substantial progress. Systematic maternity care was made available to women from early pregnancy to 42 days after delivery and more than 50 major cities began providing sophisticated perinatal care services, including prenatal intrauterine diagnosis and genetic consultations.

Much of this progress resulted from China’s rapid social and economic development, which enabled the government to invest more money and resources into MCH. By the 1980s, MCH institutions had been established, and the government invested in professional training for MCH by adding MCH specialties to medical universities. Another milestone was the development of a “MCH Annual Reporting System,” which recorded data on birth and death as well as disease incidence in MCH care. This helped China keep track of its progress and monitor the challenges it still faced.

Later in the 1990s, China announced new national legislation such as the “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Maternal and Infant Health Care” and the “National Program for Women’s Development in China” which was monumental in helping define China’s goals and updated policies for MCH. Under the law, China greatly advanced the promotion of breastfeeding practices to help reduce neonatal and early infant mortality rates and benefit the physical and mental health of the mother and child. Healthcare facilities were required to provide guidance on maternal breastfeeding and prohibited the promotion of breast milk substitutes. Hospitals were also evaluated on their baby-friendly hospital (BFH) status to help foster a more supportive environment for breastfeeding.

Critical services such as maternal and childcare hospitals and neonatal wards were established in all provinces around China. A NICU-centered active transport system was created, enhancing critical neonates’ survival rates and life quality. Many of these advancements would not have been possible without international support from multilateral organizations like WHO, UNICEF, the World Bank, and UN Population Fund, which supported various programs to improve China’s MCH.

China’s progress in the maternal mortality ratio

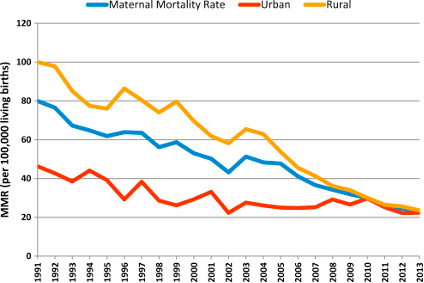

At the turn of the century, a vital health indicator to understand a country’s MCH was the maternal mortality ratio (MMR). China, along with 188 countries, signed the Millennium Declaration to achieve the eight Millennium Development Goals: Goal 5 included reducing the MMR by three quarters between 1990 and 2015, and Goal 4 aimed to decrease child mortality by two-thirds.

China achieved both goals by 2014, one year ahead of schedule. The MMR was 21.7 per 100,000 births compared to 88.8 per 100,000 births in 1990. This represented a 75% reduction in MMR over 25 years. Today, China’s MMR lies at about 16.9 deaths per 100,000 live births.

There was also progress in China’s infant mortality rate, which was at 43.2 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990 and lowered to 8.9 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2021. China has also focused on narrowing the gap in MMR between urban and rural areas. In 1990 the MMR in rural areas was twice the number in urban areas. By 2010 the gap was almost negligible. This progress can be attributed to the introduction of the Basic Public Health Service Equalization project, which aimed to eliminate inequalities in medical services and life quality between urban and rural areas.

China’s maternal mortality ratio in urban and rural areas (1991-2013) | Source: National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China

Hospital delivery rates in rural areas also improved, enhancing the quality of women’s neonatal care and reducing the risk of pregnancy-related disease. In 1990, hospital delivery rates were 1.65 times higher than in rural areas, but by 2019 the rates were almost equal.

Regional challenges in maternal healthcare

However, despite China’s remarkable progress in MCH services and care over the last 70 years, particularly in closing the gaps between rural and urban areas, there is still room for more improvement.

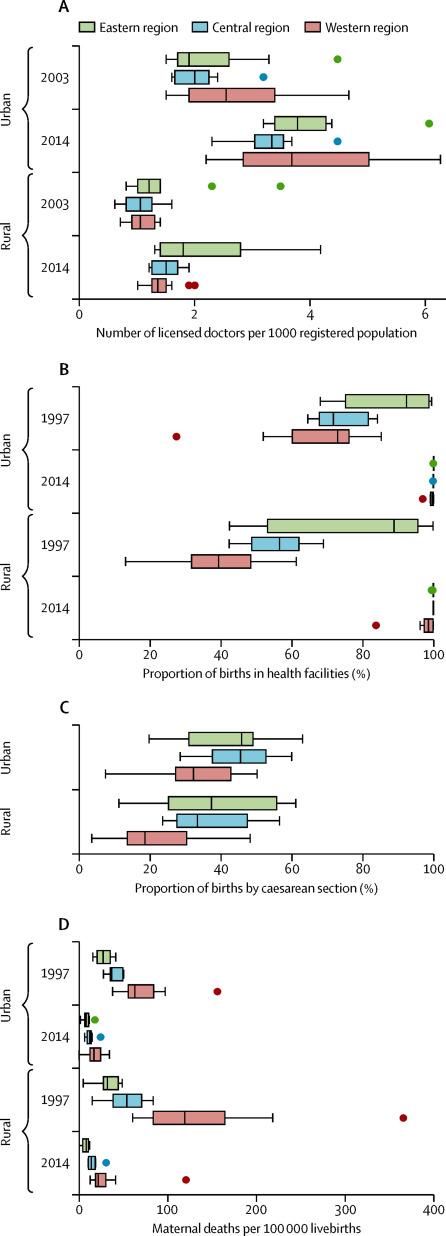

Currently, one of the biggest challenges is closing the gap between the eastern and western areas of the country. With its large population of ethnic minorities and higher poverty rates, Western China has a lower GDP per capita and higher fertility rate than eastern and central China, leading to greater challenges in accessing quality healthcare.

A survey of 42 poor counties in Western China found that most health facility births took place in county hospitals, and antenatal visits often took place in township hospitals. The capacity and quality of care in these two types of hospitals are lower than those in central and eastern China. Township hospitals especially, have low capacity for obstetric care, with limited health services and lack of adequate facilities.

Furthermore, findings showed that maternal care in the form of antenatal visits, health facility births (as opposed to traditional at-home conceptions), and cesarean sections varied with the mother’s education level. Only 44% of illiterate women gave birth in health facilities compared to 100% of women with higher level education. Similar trends follow for cesarean sections and antenatal care.

Due to its large size in both population and area, China has always struggled with the rural-urban divide in many factors of life. Over the years, this gap has grown significantly smaller regarding woman’s health. And while the east-west divide is like the rural-urban in that the East tends to be more urban and the West more rural, the West has higher populations of ethnic minorities and education levels vary more. Thus, China needs to implement the same amount of effort it put into eliminating the rural-urban gap into reducing the eastern-western gap in women’s health.

Regional variation in maternal health parameters, by urban and rural area | Source: China health statistics yearbook

Lasting effects of the one-child policy on women’s sexual and reproductive health

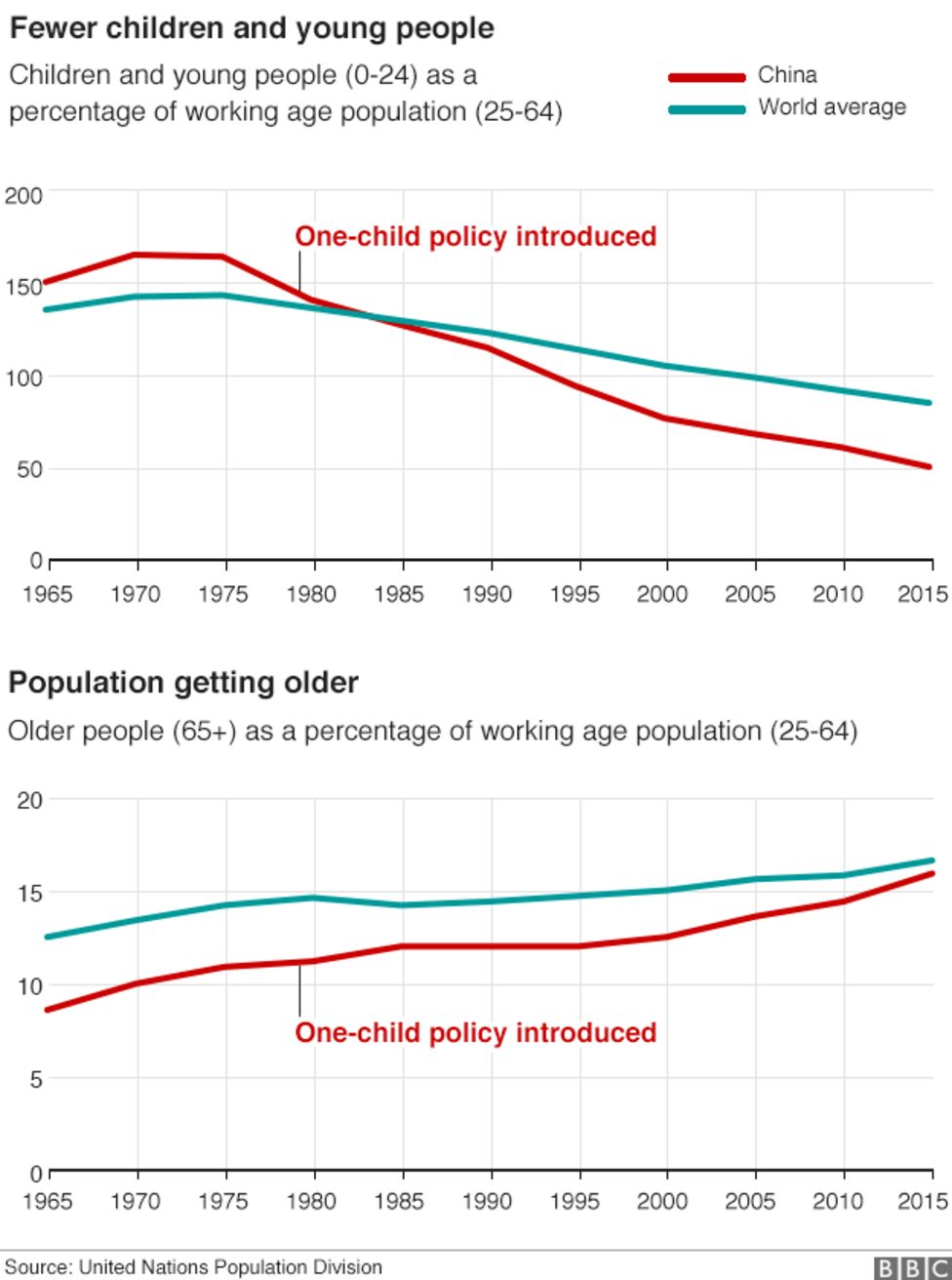

Aside from policies increasing the accessibility of women’s health services, family planning policies have had the most impact on women’s health in China. The one-child policy, a cornerstone of China’s population planning, was implemented in 1980 by the government as a nationwide effort to reduce the rapidly growing population by limiting families to having only one child. This policy was later changed to a two-child policy in 2016 and then a three-child policy in 2021 in response to the aging population and shrinking workforce.

While the one-child policy effectively lowered fertility and birth rates, women’s sexual and reproductive health freedoms was greatly affected. Enforcement of the policy was strict in certain parts of the country, and many women underwent forced abortions or sterilization and even committed infanticide. These procedures often targeted baby girls due to a cultural preference for boys. This is one of the main reasons why China currently has one of the most considerable gender imbalances in the world, with 34.9 million more males than females according to census data released in 2021.

In 1983, more than 14 million fetuses were aborted, over 16 million females underwent sterilizations, and about 17 million intrauterine device insertions were performed. Pregnant women often had to hide their pregnancies when having a second child which prevented them from accessing adequate maternal and infant healthcare. In 2011, the Chinese government estimated that approximately 400 million births were prevented under the one-child policy.

Population demographics before and after the introduction of the one child policy | Source: BBC

Despite the effectiveness of the one-child policy in achieving its aims to control the population growth; the country is now dealing with the inadvertent consequence of drastically low birth and fertility rates. Many Chinese families are now unwilling to have more than one child due to the expensive cost of childcare and education. They also cite insufficient support for maternity leave and retirement as major factors for not having children or limiting themselves to one. This is particularly important for working women who do not want to compromise their careers to have a child. A report from 2021 showed that only 5% or working mothers and 12.7% of working fathers wanted more children.

Additionally, due to improvements in healthcare and quality of life, China’s life expectancy has increased. By 2040, the population of people 60+ years old are expected to reach 28% of the population, creating further imbalance in national demographics. As the elder population grows larger, the workforce grows smaller.

Attempts to reverse this trend through the three-child policy or other measures have proven widely unsuccessful. Moreover in 2021, the State Council indicated that it would seek to reduce the number of “medically unnecessary” abortions. This statement was primarily met with trepidation by women already weary of further interference with and control over women’s autonomy over their bodies. Of course, some also supported the announcement and believed that the policy could help prevent sex-selective abortions and unplanned pregnancies.

While responses were mixed, the legacy and trauma of the one child policy remains an important aspect of Chinese society that the Chinese government must figure out how to change in order to maintain the forward direction of women’s health, and also tackle the demographic crisis.

Women’s health in a changing China

The explosive coverage of the U.S. Roe v. Wade case, in combination with China’s recent policies on reducing abortions, has triggered a response from Chinese women as they have enjoyed a drastic improvement in health yet still face policies that limit their reproductive autonomy in the face of declining population growth. Public health services, awareness and training have advanced greatly in the field of MCH in China, yet this progress cannot be detached from the legacy of family planning policies that have often compromised women’s access to health services for the sake of fixing a problem that women should not be held responsible for.

As China faces an ongoing demographic crisis, women’s health is a crucial and necessary component of improving public health. The consequences of an aging population affect both the country itself and its role and impact on the global economy. While each country has its own health policies for women’s health, China has seen major accomplishments in rapid and effective change in MCH, as well as underlying problems that other developing countries can learn from.

About The Author

Mia Landeck

Mia Landeck is a Research Analyst Intern at Bridge Consulting. With a background in social research and public policy at NYU Abu Dhabi, Mia has a strong interest in understanding the intersection of international development and policy in the Chinese context. Find Mia on LinkedIn.