How China Plans to Achieve Depression Awareness Among 85% of Students by 2022

October 12, 2020 | Christine Hwang, 2020 Fall Intern, Bridge Consulting

A Look Into China’s Recent Focus on Depression and the Higher Education Mental Health Landscape

- China’s recent national focus on depression prevention and treatment has led to much public discourse around mental health, with heightened attention to college student mental health especially.

- Mental health policy changes and campaigns have to take into account how universities communicate mental health concerns to students and families, public awareness around mental health, and protection of confidentiality while increasing screenings or other mental health services.

- Many grassroots, government-backed, and international initiatives are ripe opportunities to advance young adult mental health conversations in China. Change requires a global effort.

World Mental Health Day 2020’s goal is to increase investment in mental health, and it has been heartwarming to see global mobilization around the #MoveForMentalHealth movement led by United for Global Mental Health and WHO. In a time where COVID-19 has created mental trauma in addition to physical ones, global attention to mental health has become more imperative than ever. As a mental health advocate who grew up in both the US and China, examining China’s investment in college mental health, particularly targeting depression as a recent health focus, has proven deeply insightful. Globally, in 2016, the second leading cause of death among those aged 15–29 was suicide, and depression is currently the fourth leading cause of illness and disability among adolescents aged 15–19 years. A look at how the world’s largest developing nation is addressing a global adolescent and young adult mental health crisis is especially pertinent.

On Weibo (popular Chinese social media platform, similar to Twitter), a hashtag that has attracted more than 200 million reads recently is one on a working plan (in Chinese) published on September 11 from China’s National Health Commission around depression prevention and treatment. The plan focused on students, pregnant women, the elderly, and those in high-stress occupations, detailing comprehensive guidelines on:

- More effective general knowledge sharing on depression

- More accessible screening (with PHQ-9, a self-administered assessment)

- Early diagnosis and standardized treatment plans

- Strengthened hotline services

- Further development of crisis intervention teams

Within the plan, a widely discussed requirement is mandatory depression screenings and mental health courses for college students, under the overarching goals of achieving knowledge of depression prevention and treatment among 85% of the overall K-12 and college student population by 2022.

Active government attention to a disorder that affects 23.8% of the Chinese college student population (according to a systematic literature review in 2015) is promising given China’s record of rapid government-driven reforms (a recent case in point being nation-wide mobilization around efforts to reduce food waste). However, questions should be raised about how public understanding of mental health, implementation details, and international collaboration need to go hand in hand with top-down policy.

The College Mental Health Landscape In China

National Policy Support. Despite persistent stigma around the topic, mental health discussion and services have seen great strides over the past 15 years. Key legislature such as the National Mental Health Law in 2013 and National Mental Health Work Plan (2015–2020) have marked mental health as an important national issue. In particular, there’s been consistent policy support around mental health education in colleges, stemming from a 1994 issue (in Chinese) from the central government that paved way for more rapid development of counseling centers in universities. Most recently, adolescent wellbeing is a listed focus under the Healthy China Action Plan (2019–2030), the national health policy framework that prompted the recent depression prevention and treatment working plan.

Mental Health Services in Higher Education. Complete national data around the current status of college counseling centers and mental health education is limited, though extant data indicates a high level of attention to these topics:

- According to a 2015 article by two administrators from Xiamen University, most Chinese universities have counseling centers yet much improvement is needed in professional capacities and number of counselors available, seeing that college counseling only started to develop in the 1980s in China.

- Mental health education, on the other hand, has gained more traction. A 2018 survey for 11 higher education institutions and related mental health education workers in the country found 76.7 % of higher education institutions include mental health education as part of overall institution performance evaluations, while 96% of institutions reported they invested at least 10,000 to 50,000 RMB (1,500 USD to 7,500 USD) toward mental health education annually.

Impact of COVID-19. COVID-19 has highlighted significant national need to focus on mental health, especially among the younger generation. China’s Health Times for instance reported 18 teen suicide events around April, May, and June. China has also paid special attention to mental health crisis intervention during COVID-19, as seen from the National Health Commission’s release of related intervention guidelines in January. (You can read more about China’s focus on mental health after COVID-19 in our previous article.).

Unique Characteristics of College Mental Health Services in China

To understand major opportunities and challenges to implementing plans to educate and screen students on depression in colleges, we must first discuss key characteristics of college mental health programming in the country.

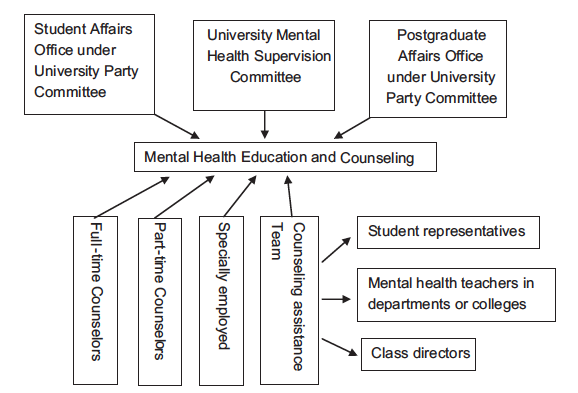

A major distinction for mental health services in Chinese universities from programs in the West is its close link with civil education (思想政治教育). Mental health education happens largely through lectures run by mental health teachers in counseling centers. A survey on mental health service center management in some universities showed 77.8% of centers were managed by the student affairs office, which is also responsible for civil education. While this framing for mental health education can help emphasize its importance to educators, there is also possible risk that such a curriculum detracts from the goal of supporting student’s varied emotional needs and normalizing mental illness.

Another unique approach in China’s college mental health services, at least on a theoretical level, is the close involvement of family and medical systems. Whereas, for example, counseling centers in the US are run on an individual help-seeking basis separate from contacting family unless in urgent situations, in China, parent input on student mental health and crisis intervention decisions is highly valued, even over those of professionals. Any reform in existing mental health programming or advocacy campaigns should take into account the importance of family decision-making and family education around mental health in this cultural context.

Challenges For the Recent Policy

Implementing this policy from a logistical standpoint, including considerations for screening resources and treatment availability in light of low numbers of therapists and psychiatrists (there are 23,000 psychiatrists in China, or just 1.7 per 100,000 people, compared with 12 per 100,000 people in the United States), will be a huge challenge. Beyond that, how mental health information is talked about and spread among the public warrants more discussion.

Stigma. Mental health stigma, which manifests in different ways across countries, is still very present in Chinese society. While recognition of depression is the highest among other mental illnesses in China, a common misconception for someone with depression is that they are too delicate or have “nothing better to do.” A mental illness label could isolate someone from their community if the culture around mental health conversations doesn’t change along with policy changes.

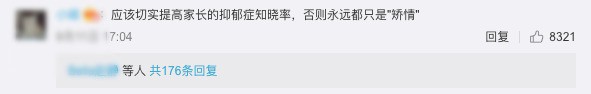

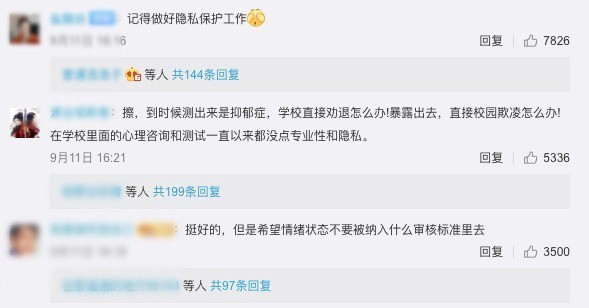

Confidentiality Concerns. Public response to the policy on depression screening, which specifically mentioned “establish student mental health files” and “pay special attention” to students with abnormal evaluation results, expressed major confidentiality concerns, a huge deterrent for help-seeking in colleges. While the top comments under a People’s Daily post on the policy expressed support for greater attention to student mental health, below those comments was an indignant complaint of how a test result indicating depression could lead to stigmatization from the school and bullying from peers. Concern was also expressed about how “emotional state evaluations” might be inappropriately involved in other evaluation standards for students. Ensuring mental health information does not lead to employment discrimination is another important consideration. According to a 2020 national college student health survey by www.dxy.com (a widely used online platform for medical knowledge and services) and China Youth Daily, only 6% of students listed seeking professional help as a way to cope with pressure.

Scaling Up. Finally, major gaps still exist in mental health services between rural and urban areas. There is need for improvement in the focus of mental health across different populations, such as those coming from different economic backgrounds or the LGBTQ community. The government, institutions, and civil society organizations need to consider how this recent policy can be implemented in different infrastructural contexts.

Opportunities for Mental Health Moving Forward

At the same time, public involvement in college mental health advocacy and awareness has surged over time, setting the groundwork for further conversation and policy movement around mental health.

Grassroots Involvement. Mind China (心声) is a great example of a local mental health awareness NGO that focuses on student mental health among other topics. Founded by students from Harvard University, Columbia University, University College London, Fudan University, and East China University of Political Science and Law in 2018, they focus on youth entrepreneurship, mental health advocacy, and sustainable development of mental health initiatives and research in the country. Though still up and coming, they have already established online networks connecting students and stakeholders passionate about mental health, with an active mental health club in Fudan University.

Public Campaigns. May 25th is a dedicated holiday for college student mental health, supported by the Ministry of Education and established in 2004 by the Central Committee of the Communist Youth League and All-China Students’ Federation. This year’s holiday featured a conference with major stakeholders and universities on how to meet student mental health needs in a “post-COVID” era in China.

International Efforts. In addition, there are opportunities for international collaboration in mental health education and prevention. UNICEF China, for instance, has rolled out initiatives to promote social-emotional learning programs in primary and secondary schools, especially in rural areas. In the case that confidential student mental health files can be established, Chinese universities may also seek opportunities to learn from other countries and build up a stronger research database around student mental health. As an example, more communication with the WHO World Mental Health International College Student (WMH-ICS) Initiative, a global initiative focused on needs assessment and interventions for college student mental health, could be beneficial both for China and the international community.

COVID-19 has brought forth unprecedented momentum for reform and change, and with this year’s World Mental Health Day and #MoveForMentalHealth movement, an expanding global community is focused on investment in mental health. In addition to the evolving global context, the opportunity for addressing China’s college mental health crisis has never been greater given the build-up of government and public attention toward depression and mental health education. Beyond policy mandates for mental health courses and screening, more public awareness and cross-sector coordination, as well as international cooperation and mutual learning, are needed to properly advance China’s mental health agenda and leap closer toward global mental health for all. From simple conversations to global campaigns, we all can play a part in making it happen.

About The Author

Christine (Yi Ting) Hwang

Christine Hwang is an aspiring global educator majoring in Human Development & Psychology at Northwestern University. She is passionate about social equity, and completed a Fall internship with Bridge Consulting in 2020. Check out her earlier pieces and follow her on Medium here.