China’s polio eradication efforts and its impact at home and abroad

Families lining up to receive the “sugar pill” | Source: CGTN

June 22, 2022 | By Celine Chen, Senior Associate, Bridge Consulting

Speaking at the recently concluded 75th World Health Assembly in May 2022, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said: “Our dream of a polio-free world is tantalizingly close, with four cases of wild poliovirus reported so far this year in Afghanistan and Pakistan – although two new cases in Malawi and Mozambique are a setback.” Flashback to 1988 – the year the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) was launched at the 41st World Health Assembly when more than 100 countries reported a total of 350,000 cases – this recognition is indeed a monumental achievement in the fight against infectious diseases.

As one of the countries that has eliminated polio, China was officially certified as polio-free by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2000. But the country’s investment in polio elimination did not stop there. During and after its campaign, China has accumulated rich experience in this field – from polio vaccine development and production, to progressive vaccination strategies, modern laboratory practices and effective monitoring.

China’s success in polio elimination and maintaining a polio-free status is not just a story to tell. Instead, it is a vital opportunity for the country to deepen its health cooperation with other countries and follow through with its ambitions of being a more prominent global health player by sharing lessons learned, expertise acquired, and vaccines developed to contribute to the worldwide polio eradication campaign, especially in countries where polio continues to exist.

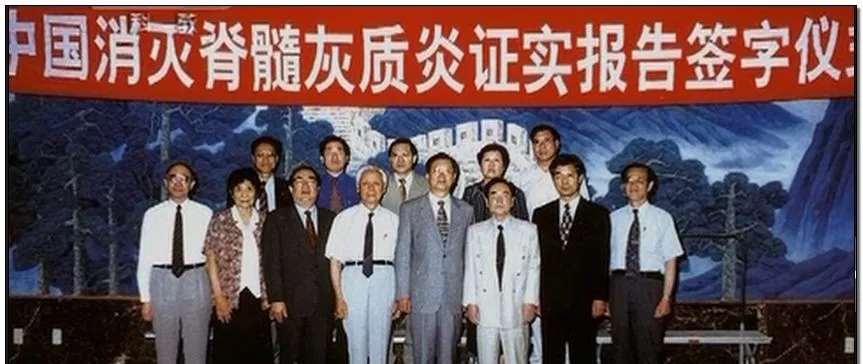

Signing Ceremony of China’s Polio Eradication Confirmation Report, held at China’s Ministry of Health. Gu Fangzhou, 74, signed on the report as a special representative.

Source: Peking University

Developing the sugar-coated pill vaccine and a national immunization program

In the early 1960s, China reported 20,000 to 43,000 polio cases annually, making it one of the significant endemic countries of that time. To eliminate polio, China began by sending a team of researchers to the former Soviet Union to study polio vaccine preparation. After returning home, they used their limited resources to set up a laboratory and develop the first live attenuated oral polio vaccine in China. With this, Gu Fangzhou led the team to create an oral polio vaccine often referred to as the ‘sugar-coated pill vaccine’.

For eliminating polio, it’s essential to maintain efficacy of the vaccines by ensuring a cold chain. The vials need to be kept in the ambient temperature of two to eight degrees Celsius. However, it was impossible to provide a freezer to vaccines in-transit or in non-electrified rural areas in those days. Gu’s team solved the challenge by developing the sugar-coated pill that tasted good and was also easy to preserve. The vaccine reduced incidence rate of the disease by nearly 100 times from 1949 to 1993, saving millions of children from crippling paralysis.

However, to achieve the goal of polio elimination, having a vaccine was not enough, mass vaccination was needed to ensure that the population became immune to the virus. From 1965 to 1977, the annual number of reported polio cases in China ranged from 4,500 to 29,000 [9]. After the introduction of planned immunization and its inclusion of polio vaccines in 1978, the number of polio cases in China declined significantly to 667 reported polio cases in 1988. Subsequently, from the late 1980s to the 1990s, local authorities proposed that the immunization rate of children should reach the target of 85% in units of provinces, counties, and townships. From 1993 to 1995, China carried out two rounds of childhood polio vaccine booster immunization campaigns for children under four years old every year. National leaders would attend each event, showing the government’s high prioritization, which significantly increased school-age children’s vaccination rate and reduced polio cases from 4,623 in 1989 to 165 in 1996. In 1994, China reported its last case of indigenous wild poliovirus.

Two-and-a-half year old Wei Sining children taking “sugar pills” at a kindergarten in Urumqi City, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, March 2, 2006.

Source: People’s Pictorial

Moreover, the contribution from GPEI partners was an added factor to the successful completion of the mass polio vaccination in China. In 1993, WHO estimated that China needed at least 410 million to 510 million units of vaccine to complete polio booster immunization activities, yet China produced only 325 million units of vaccines at that time. To ensure that China’s intensified immunization activities were not affected by the shortage of vaccines, international organizations such as Rotary International and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) donated a total of 120 million units of polio vaccine.

The AFP case surveillance system and polio vaccine immunization strategy

But how is a polio case identified in the first place? The first symptom of polio is a type of paralysis known as “acute flaccid paralysis” (AFP). Accordingly, patients who suddenly develop AFP are considered potential polio cases. Establishing and improving the AFP surveillance system thus played an essential role in eliminating polio in China, especially in helping the country maintain a polio-free status.

In 1991, China established a national AFP case surveillance system, which adopted a unified case definition, and carried out active case surveillance and “patient zero” reporting. Since then, the surveillance system has gradually improved in quality. In October 2011, China launched an improved AFP Case Surveillance Information Reporting Management System on the China Disease Control and Prevention Information System platform, which allowed for direct reporting from the surveillance information network, and guaranteed the maintenance of the polio-free status.

In addition to wild poliovirus, the world remains at risk of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus transmission. Thus to reduce the risk of vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP) and vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV), China has continuously optimized and adjusted its vaccine immunization strategy per WHO requirements and in light of its progress in polio elimination. In May 2016, China altogether discontinued the trivalent oral vaccine, replacing it with a bivalent oral vaccine (bOPV) containing types I and III, and started introducing one dose of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV). In January 2020, the immunization program was adjusted again to 2 doses of IPV plus two bOPV doses.

China’s polio vaccine R&D and technology production

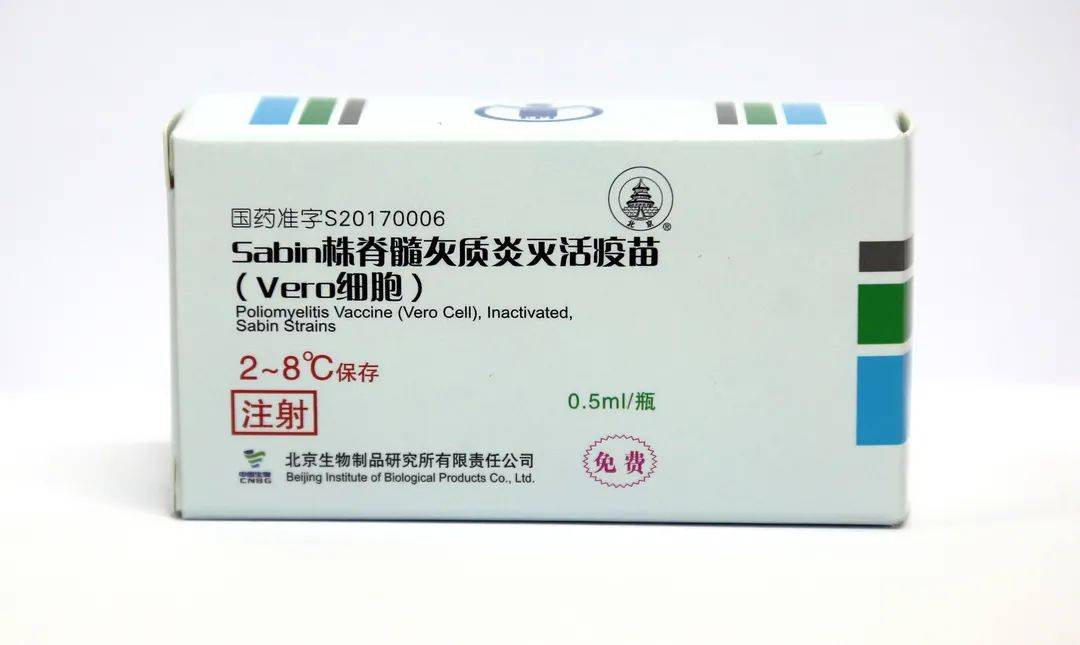

The continuous breakthroughs in China’s vaccine R&D and technology production have helped ensure smooth transitions within its polio immunization program. The development of a Sabin-strain polio inactivated vaccine (sIPV) by the Institute of Medical Biology at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and the Beijing Institute of Biological Products (BIBP) of Sinopharm broke the preconception that only developed countries were able to produce inactivated polio vaccines.

In addition, BIBP was the first to adopt a bioreactor culture process based on sheet carriers, that could enable high-density and static culture. They took the lead in addressing technical challenges of scaling up, breaking through production capacity bottlenecks, and achieving large-scale production, resulting in an annual output of up to 30 million doses of sIPV.

Sabin strain inactivated polio vaccine (sIPV) sample.

Source: Sohu

Complementing efforts of GPEI on the worldwide front

Despite scarce resources and a large population, China’s achievement with its polio-free certification marked an important milestone in the global polio eradication campaign. It not only boosted the confidence of other developing countries in eliminating polio but also allowed China to share valuable lessons learned, expertise acquired, and vaccines developed with other nations. Consequently, over the past decade, China has contributed to global polio containment by dispatching experts, providing vaccines overseas, and more.

- Experts dispatched to provide technical support for polio eradication

In the prevention and control of various infectious diseases, China has accumulated significant experience in vaccination, infectious disease surveillance, and laboratory testing techniques and is now able to provide such technical support to other developing countries.

For instance, in 2011, China carried out its first overseas public health assistance, sending disease control experts to Namibia and Nigeria to participate in their polio containment campaign. While assisting the local prevention and control work, the experts put forward constructive suggestions for improving local disease surveillance, enhanced immunization, and other immunization planning work. Zuo Shuyan, an official at the WHO Representative Office in China at the time, said: “I hope more Chinese experts will go abroad to support polio eradication in countries where the epidemic is still endemic. In addition, I also highly hope that China will use bilateral and multilateral channels to deal with polio, providing key countries such as Pakistan and some African countries with financial, equipment, and technical assistance.”

- bOPV is pre-qualified by WHO and can be supplied globally by multilateral organizations

According to GPEI’s risk assessment of vaccine supply, the number of OPV suppliers worldwide is currently limited and, in fact, decreasing. As the COVID-19 epidemic continues, more vaccine-related resources may be devoted to COVID-19 relief programs, further threatening the global supply of OPV.

With the support of GPEI partner Gates Foundation and other institutions, the bOPV developed by BIBP passed WHO pre-qualification in 2017 and reached long-term procurement agreements with multilateral organizations like UNICEF, bringing about the first large-scale export of 70 million doses. At present, the vaccine has been supplied to South Sudan, Uganda, Zimbabwe, and other countries to help build polio immunity barriers.

Sinopharm Group exported bivalent polio vaccine (bOPV) to South Sudan (January 2019). | Source: Sinopharm

- sIPV has passed WHO pre-qualification, supporting the adjustment of the global immunization strategy

To remove the risk of reactivation of the vaccine virus through OPVs, GPEI plans to phase out OPV globally with the use of IPV after eliminating wild poliovirus type I and vaccine-derived type II poliovirus. However, due to low production capacity and high cost, the resulting IPV supply shortage will challenge this strategy adjustment.

In February and June this year, BIBP and Sinovac received pre-qualification from WHO for their sIPV respectively. This means that the inactivated polio vaccine developed by China can be distributed to the rest of the world and contribute to the global eradication of polio.

Eradicating polio in Pakistan and Afghanistan

According to the GPEI’s Polio Eradication Strategy 2022-2026: Delivering on the Promise, the overarching global goal is to permanently stop all transmission of all polioviruses in Afghanistan and Pakistan, the only two remaining polio-endemic countries.

Wang Yi meets with Foreign Minister Bilawal of Pakistan.

Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China

On 22 May 2022, Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi held talks with visiting Pakistani Foreign Minister Bilawal. The two sides agreed to deepen all-around practical cooperation and promote the construction of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Previously, Pakistan also responded to the Global Development Initiative proposed by President Xi Jinping by joining the “Group of Friends of Global Development Initiatives” to implement the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goals.

With economic development and health complementing each other, the construction of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor is also inseparable from improving health and well-being. In this regard, China can play a unique role in blocking the spread of wild poliovirus in Pakistan and even Afghanistan, which can become a concrete action under the Global Development Initiative and tangible progress toward building a global community of human health.

As early as 2011, when dealing with the polio epidemic imported from Pakistan in Xinjiang, Wang Yu, the former director of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC), once proposed: “In the China CDC’s next step for international cooperation, the eradication of polio in Pakistan should be taken as a main priority. In addition to the immunization experts from the National CDC, experienced experts from various provinces will be invited to work in Pakistani regions where conditions permit, including in polio training, system construction, and helping them conduct laboratory analysis and surveillance.”

Ten years later, in 2021, Wang Yu, serving as an expert advisor to the Boao Forum for Asia Global Health Forum Conference, once again put forward: “Chinese public health experts have traveled to Africa and Pakistan to participate in the global polio eradication campaign, and have accumulated valuable experience. We should pay much attention to it and look to participate more actively.”

Even as COVID-19 continues to rage across the world and consume valuable health resources, China can consider sharing their vaccines, technology, and experience accumulated in the polio containment campaigns with Pakistan and Afghanistan through GPEI and regional and bilateral cooperation. This will not only help the world achieve the goal of polio eradication but, at the same time, also improve global health security and create favorable conditions for the world to overcome COVID-19 and prevent future infectious disease outbreaks.

About The Author

Celine Chen

Celine has over 5 years of work experience in the field of public health. Before re-joining Bridge, she was a health program officer for Save the Children (SCI) and earlier to that as a communications coordinator in the Beijing office of the Asian Liver Center at Stanford University. With her passion for public health, particularly infectious diseases, she will soon start her Masters in Public Health program with Peking University.