These Two Afghan Wheelchair Basketball Players Thank Polio for Giving Them Opportunities

October 24, 2023 | Andre Shen, Founder & CEO, Bridge Consulting

When you mention Afghanistan, you may immediately think of terrorism, war, poverty, and, given my background, I would add one more thing—polio. This disease, which primarily affects children under the age of five and can cause paralysis and even death, is currently endemic in only two countries, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

A little over ten days ago, during a meeting with Najum Iqbal, Head of Communications at the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) East Asia Regional Delegation, I learned that their organization would sponsor the Afghan wheelchair basketball team to participate in the 4th Asian Para Games in Hangzhou. I inquired if there were any players in the team who were disabled due to polio, and he immediately confirmed, “Yes, there are a few.” This piqued my curiosity, and I requested to meet these athletes when they arrived in Hangzhou. He readily agreed to my request.

A First Impression That Differed From Expectations

Last Friday, on October 20th, I arrived in Hangzhou and met Sayed Wasim Sadat and Fawad Samadi. I had asked the ICRC staff where I should meet the athletes, and they said it didn’t matter as long as it was close to the Para Games Village since they had to use wheelchairs for mobility. However, when I saw them, neither of them were in wheelchairs, and they weren’t even using crutches. Their legs appeared uninjured (later, I found out that they had received orthopedic treatments). I started to wonder if I should confirm whether they had actually been affected by polio or not.

I held back from asking because both of them nodded in response when I mentioned the word “polio.” However, my doubts persisted because they nodded but didn’t add anything. Instead, after I brought up the name Bill Gates, they began discussing their knowledge of him, which unsurprisingly revolved around Microsoft and wealth, rather than his long-term support for global polio eradication.

The interview with the two of them began amidst my various doubts and nervousness.

I was speaking with Sayed Wasim Sadat in the Asian Para Games Village Media Center (photo taken and provided by Najum Iqbal)

A Personal Account That Didn’t Follow the Script

Sayed Wasim Sadat was born in Nangarhar province, and later moved to Kabul with his family. He contracted polio in Pakistan at a very young age. At that time, when he was running a fever, his parents took him to a hospital where he was given medication. For the following 7-8 months, he was bedridden. On the other hand, Fawad Samadi has been living in Kabul and became disabled at the age of 2 due to polio, which left him with a leg disability.

I asked them to share how polio had changed their lives and the challenges of playing wheelchair basketball. However, they both mentioned that polio didn’t change their lives because they were so young when they fell ill, and they had little memory of life before polio. Neither of them saw polio as a misfortune; on the contrary, they felt grateful for it. Fawad even considered polio a gift from Allah and happily accepted it.

Regarding the challenges of playing wheelchair basketball, they didn’t talk about the inadequate facilities and equipment, physical limitations, or the hardships of training as I had expected. Rather, Sayed Wasim told me that his biggest challenge was coordinating his training, university classes, and work.

Sayed Wasim Sadat in the Hangzhou Asian Para Games Village (photo from his personal Instagram account)

He worked during the day, and basketball training and school courses were held in the evening, making it impossible to do both at the same time. He sought advice from friends, and they advised him to alternate between basketball practice and attending university. Later, he spoke to his teacher, explaining that he had been selected for the national team and needed to complete training to represent the country in competitions. His teacher granted him special permission to study at home when he couldn’t attend classes, allowing him to catch up on his coursework for two hours every night after practice.

Isn’t this a challenge that many of us experience too? We switch roles in different contexts every day, wanting to excel in every role, but our limited time and energy makes it challenging to juggle everything. We all need wisdom and courage to make choices.

They also emphasized the importance of friendship. “A friend is a brother from another mother,” Sayed Wasim defined it this way. He is 26 years old and still single, so he doesn’t know the meaning of having a wife yet. However, he values friendship, trusts his friends, and always seeks their advice. Friends help him dispel doubts and negative emotions, providing a positive perspective on things. He now has about two half-days of leisure time each week, which he primarily spends with friends.

Fawad believes that healthy relationships are essential for a happy life, and friendship means life to him. He said life is like a series of steps, and now he is on the step of representing Afghanistan in international competitions, with his teammates being his best friends. I asked him what the next step is, and he laughed. With a mischievous grin, Sayed Wasim sitting across from him encouraged me to keep asking. I inquired, “Is it getting married?” Fawad continued to smile. Although he’s two years younger than Sayed Wasim, he is already looking forward to marriage.

Finally, I asked them, “There are probably many others around you who are disabled due to polio, right? Are they as optimistic as you? Do they also consider it a gift from God?”

“I’m only saying that polio is a gift to me, but in Afghanistan, many people cannot lead a normal life because of polio,” Fawad said. “We are very fortunate because polio has given us more opportunities, but for many others, the disease has a negative impact. I want polio to end for good from Afghanistan and other countries.”

Fawad Samadi inside the Hangzhou Para Games basketball gym (photo from his personal Instagram account)

The Final Push to Eradicate Polio

At the 1988 World Health Assembly, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) was officially launched. Since then, global polio cases have decreased by 99%. Last year, only 30 cases of wild polio were reported worldwide.

Despite remarkable progress in reducing global cases, GPEI repeatedly missed its polio eradication target dates. When it was founded, GPEI partners set the year 2000 as the target date, and the latest goal was to end all types of polio virus transmission by the end of this year. Unfortunately, just over a month ago, GPEI issued a statement acknowledging the evaluation by the Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) and admitting that more time is needed to achieve this goal.

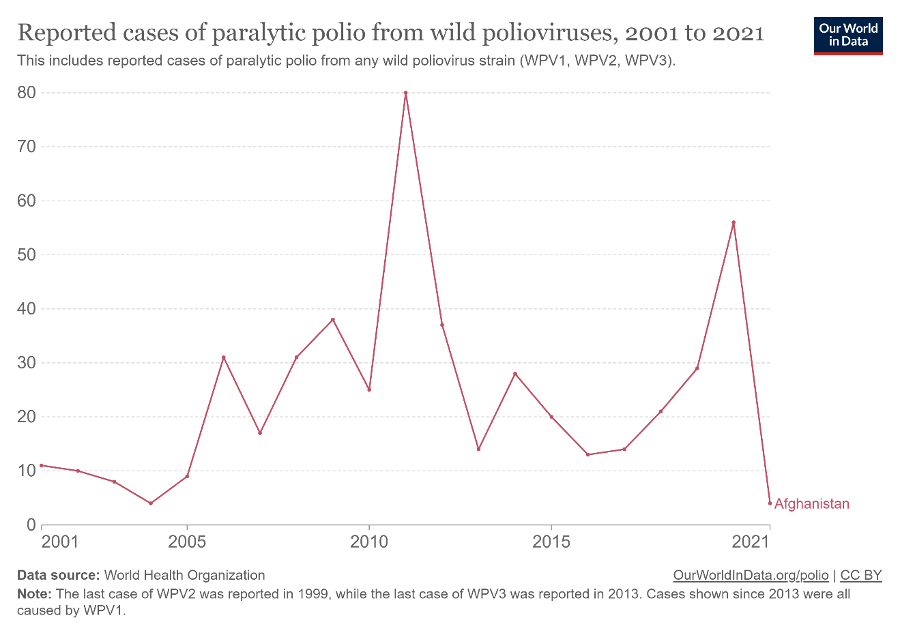

Progress in polio control in Afghanistan has also been inconsistent. Over the past two decades, the country has seen fluctuating case numbers.

Wild polio case numbers in Afghanistan from 2001 to 2021 (chart generated from Our World in Data website)

In its Polio Endgame Strategy 2019-2023, GPEI expressed concerns about the ban on house-to-house immunization in Afghanistan, stating that it “compounded the problem of inaccessibility.” In 2019, the Taliban authorities approved the continuation of polio vaccination activities in Afghanistan, but this didn’t immediately result in a decrease in case numbers. Instead, the country reported 29 and 56 cases in 2019 and 2020, respectively, 90% and 75% of which originated in areas not currently accessible for vaccination.

Despite the COVID-19 pandemic in 2022, Afghanistan reported only 2 cases of polio throughout the entire year, marking a historic low. However, in the first half of 2023, this number increased to 5. This demonstrates that the polio epidemic is influenced by multiple factors rather than a single cause.

Creating Opportunities Is Just as Important as Eradicating Polio

During my two days in Hangzhou, I also attended an exchange event between the Afghan wheelchair basketball team and Zhejiang Sci-Tech University’s basketball team, as well as a CBA (Chinese Basketball Association) player named Chen Zi’an. The day before, I had only interviewed two athletes, but this time, I met all the team members. As they got off the bus, using wheelchairs or crutches, it became clear to me that this was indeed a team composed of people with disabilities.

Players of the Afghan wheelchair basketball team interacting with players of Zhejiang Sci-Tech University’s basketball team sitting in wheelchairs

Years of conflict have led to the displacement of thousands of Afghans and made the country, with a population of approximately 40 million, one of the countries with the highest proportions of disabled people in the world. According to the Model Disability Survey of Afghanistan implemented by the Asia Foundation with technical support from the World Health Organization, the disability rate among adults aged 18 and over is as high as 80%.

Sayed Wasim and Fawad have witnessed far too much misfortune around them. They mentioned their experiences with ICRC’s orthopedic centers, how they have helped others, and encounters with people much more severely disabled than themselves. They’ve also met many people who wanted to take their own lives. With the help of ICRC, they were fitted with suitable prosthetic limbs, received education and vocational training opportunities, and a decent job. They have even improved their physical fitness through wheelchair basketball and have the chance to represent their country in international competitions. These experiences are aspirations that are nearly unattainable for most people living in their country.

“Disability always means challenges, especially in a country like Afghanistan, where there are already many challenges. Physical disabilities mean facing additional challenges,” Fawad said.

As I concluded my interview with Sayed Wasim and Fawad and prepared to leave the Asian Para Games Village, they began discussing “business opportunities” with me. Sayed Wasim, who speaks better English, elaborated on his university major and work experience, as well as the work related to immunization carried out by ICRC in Kabul. He asked if we could become friends on Instagram and WhatsApp, and if I or anyone I know in the future wants to do polio-related projects in Afghanistan, they’re more than willing to help.

At that moment, I realized that I didn’t need to search for commonalities between us. In fact, from the interaction we had, not only do we share the common challenge of balancing our schedules, but we also share a similar eagerness for seizing opportunities. Before coming to Hangzhou, I was focused on how to promote polio eradication by telling their stories. However, what I am pondering now is how to create opportunities for everyone, regardless of where they are or their physical condition, to lead a healthy and productive life.

About The Author

Andre Shen

Andre has been working in the social good sector in China for over a decade, building strategic partnerships with the government, multilateral organizations, NGOs and foundations, as well as digital influencers in promoting global health and development. In early 2016, he founded Bridge Consulting, an independent, mission-driven, issue-based strategy and communications consulting firm which helps clients achieve their long-term goals in China while advancing the public good through communications and advocacy.