Vaccination trends among China’s elderly from COVID-19 to flu: How to avoid a catastrophe

Elder receiving a COVID-19 vaccine shot in Shanghai, May 2022 | Source: Caixin

January 5, 2023 | Stefania Jiang, Associate, Bridge Consulting

As the COVID-19 outbreak escalates across China, one of the best solutions to protecting vulnerable populations from severe or fatal illness has been a renewed focus on vaccination campaigns.

In early December 2022, as China made its move away from the zero-COVID strategy by introducing the ‘Ten Measures’ to optimize COVID-19 epidemic prevention and control measures, boosting the vaccination drive for elderly was listed as a top priority. Reportedly, the central government was putting pressure on local governments to get 90% of those over 80 years old fully vaccinated with a booster by the end of January 2023. As of late November however, only 40.37% of those over 80 years old had been boosted.

The problem remains as this low vaccination rate – primarily attributed to vaccine hesitancy and other social factors – has been forecasted to lead to over a million deaths by year’s end. And with the winter season reflecting a severe uptick in influenza, the question remains on how vaccination against these pressing infectious diseases can be boosted among the elderly to avoid a devastating public health catastrophe? This article will explore the potential ways that the vaccine industry, policymakers and healthcare workers can collectively address the problem of vaccine hesitancy among the elderly to boost vaccination rates.

Vaccine hesitancy among the elderly during COVID-19

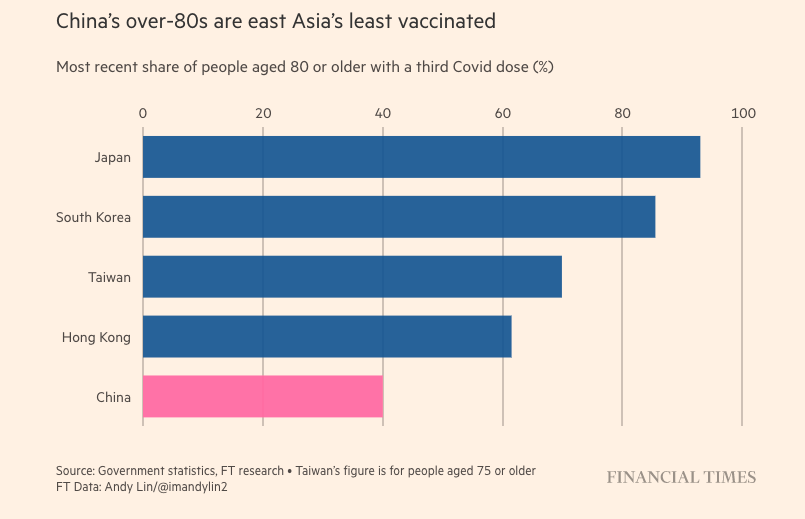

Vaccination rates for the elderly have been deceptively low. As of November 2022, only 40% of those over 80 years old had received three shots of a Chinese vaccine – the dosage recommended to have high levels of protection against the highly transmissible Omicron variant. This has meant Chinese elderly over 80 years old are East Asia’s least vaccinated when compared with Japan (93%), South Korea (85.5%), Taiwan (69.9%, for those aged 75+) and Hong Kong (61.5%).

Why is this? Let’s begin by examining the policy approach.

Comparison of COVID-19 vaccination rates among the elderly aged 80+ across East Asia | Source: Financial Times

The first problem lied in poor policy measures and lack of clear science-based messaging. Unlike a number of Western countries where vulnerable groups such as the elderly population were encouraged to get vaccinated first, in China other groups were prioritized, with China only including the 60+ population from April 2021, months after first roll out in December 2020. Lack of clinical trial data of the widely used inactivated COVID-19 vaccines with elderly participants contributed to unclear vaccination guidelines that warned elderly people with stable chronic conditions to delay or avoid the shot all together. This created much confusion early on, causing elders to hesitate in getting vaccinated out of concern of potential side effects. Lack of data has similarly prevented other groups, like pregnant women, from being recommended for COVID-19 vaccination. In the roll out, poor logistics also played a role in low vaccination rates, with many elderly being hard to reach through the typical systematic outreach (e.g., vaccination through schools or place of employment), and eventually left outside of these mainstream vaccination campaigns.

The second obstacle was the knowledge gap. Most elderly in China are unfamiliar with vaccines, as prior to the pandemic, adult vaccination lacked publicity, and most vaccines were generally self-paid. Adult family members or guardians with their own views also had a heavy influence on their use of vaccines: often times acting as the elders’ health decision-makers, they project their own vaccination hesitancy onto the elders. Moreover, low COVID-19 mortality rates achieved due to the zero-COVID policy gave the elderly’s an impression of a low risk of exposure to COVID-19.

As a result, different actors within the healthcare ecosystem – ranging from the health authorities, to healthcare providers, and family caregivers – have all had a role to play in supporting and encouraging the elderly to get the COVID-19 vaccine throughout the pandemic.

Even as people have become more willing to get inoculated compared with previously when domestic vaccines first became available in late 2020, experts have suggested that more can be done to further overcome vaccine hesitancy and achieve better results for booster coverage. This includes integrating healthcare and disease prevention services to improve services, and encouraging medical staff to raise awareness and address misinformation.

On November 29, almost a month after the ‘Twenty Measures’ were published to tackle and improve the problems caused by zero-COVID, elderly vaccination and a number of these hesitancy issues were finally addressed with the National Health Commission (NHC) unveiling new measures to boost vaccination rates among seniors:

- Elders can now take their boosters after three months following their last shot – shortened from six months previously.

- In order to widen the outreach, authorities can now implement vaccination plans to reach elderly in key places (e.g., nursing homes, elderly fitness and entertainment venues, as well as in large-scale activities, and group tours).

- To reduce possibility of adverse reactions in people with underlying conditions, medical personnel are now instructed to scientifically identify which cases should avoid or delay getting vaccinated, including those with serious allergic reactions, or with acute infectious diseases already at a fever stage. More on-site vaccination services and a post-vaccination observation period are to be offered for the disabled and semi-disabled elderly.

- Finally, to educate the elderly and their families, there will be improved communication and publicity on the efficacy of vaccines via official media and experts’ lectures.

Elder receiving CanSino’s COVID-19 inhaled vaccine in Lijiang | Source: Lijiang News

Seasonal influenza: policy recommendations targeting the aging population

Fact box: seasonal influenza | Source: Jiang et al. (2021)

- Seasonal influenza is an acute respiratory infection caused by influenza viruses (especially type A and B), which circulate in all parts of the world all year round, but mainly during spring and winter in temperate regions

- Recurring symptoms include a sudden onset of fever, cough, headache, muscle and joint pain, severe malaise, sore throat and runny nose, escalating to severe illness or death especially in high-risk groups

- According to the World Health Organization (WHO), seasonal influenza was estimated to cause about 3 to 5 million cases of severe illness, and about 290 to 650 thousand respiratory deaths annually worldwide

Influenza has been the only comparable disease to COVID-19 in terms of a need for vaccination as the best defense against severe illness. And like for COVID-19, despite their high risk of exposure, Chinese elderly have some of the lowest influenza vaccination rates worldwide. As of August 2022, only 21.7% of people aged over 60 were vaccinated against flu in China – an extremely low figure when compared with past vaccination rates of people aged 65 and over in OECD countries: England (81%) on the high end or even Germany (38.8%) on the low end.

Issues that have affected the vaccine uptake among elders have been a bit different. Aside from low public awareness of influenza and lack of coverage, the main issue relates to the cost of the vaccines. A study found this the most influential in hindering vaccinations for many elders, as compared to knowledge or awareness of vaccines. Issuing a free vaccination policy can be an important factor to widening coverage. While some cities have introduced free vaccination programs for flu (e.g., Beijing since 2007), a systematic and nation-wide program is not yet available – which would benefit the population at-large having consistent regulations.

At the same time, other practical measures need to be made, such as encouraging medical staff to recommend influenza vaccination to improve public awareness, and setting up temporary vaccination sites at elderly care institutes to improve accessibility.

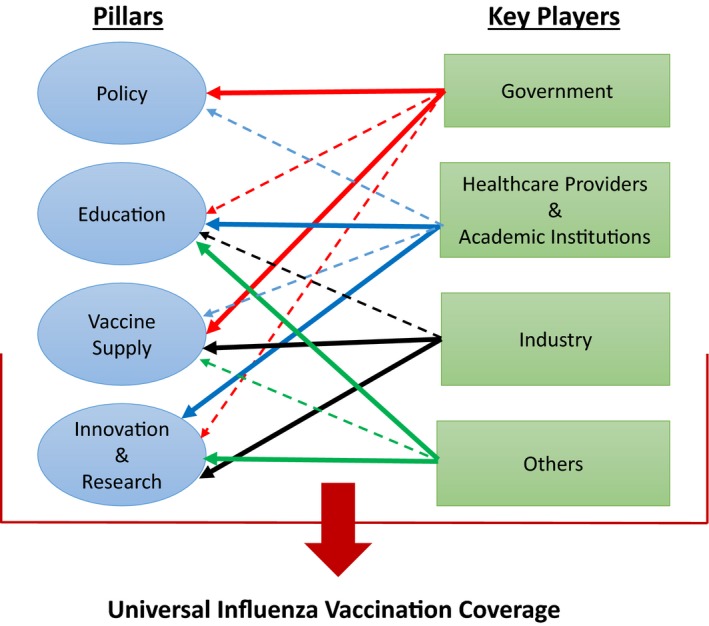

In proposing substantive structural changes towards universal influenza vaccination coverage for seniors and other vulnerable groups in China, a joint study provided policy recommendations on how to involve different players within the vaccine ecosystem. This means appropriate policies to enact influenza vaccination mandates on the elderly and provide them with insurance payment. It also means the education of healthcare providers, a sufficient supply of quality vaccines, and innovation and research for a nationwide surveillance system, new and efficacious vaccines, and strategies to boost immune response.

Policy recommendations on universal influenza vaccination coverage for seniors | Source: Li and Leng (2020)

Recommendations for a path forward

China has one of the world’s fastest-aging societies today. More than 264 million Chinese residents are aged 60 or over, which will almost double to 402 million by 2040. The China’s 2030 Healthy Initiative has highlighted that the elderly should receive vaccinations and enhance the management of chronic diseases for voluntary disease prevention. Nevertheless, low vaccination rates among the elderly remains a problem that still persists to the present day – as seen with seasonal influenza and, more recently, COVID-19.

A lot of this may have to do with their sources of information, whether from traditional media and receiving advice from trusted relatives and friends. But also, from the education of healthcare workers who play a major role in shaping public opinion and awareness of the benefits and risks of the vaccines. But overall, a low vaccination rate among senior residents in China is not only a scientific problem, but rather a social issue.

- For flu, there is sufficient clinical data to prove efficacy and safety among older people. Yet, implementation policies are inconsistent which ultimately affect the end results. Hence, taking a systematic approach can improve the coverage of seasonal flu vaccination (e.g., adopting a free vaccine policy, integrating seasonal flu vaccination into primary health care system and public health service package).

- For COVID-19, the issue has been highly politicized with often times an overexposure of information and yet a lack of clinical trials data in elderly participants and pregnant women. Hence, the role of health authorities, healthcare providers, and family caregivers in supporting and encouraging the elderly to get COVID-19 vaccines during and at the turning point of the pandemic is crucial.

Three years into the pandemic has brought valuable lessons on how to improve vaccination rates for the elderly. Overall, it is a matter of collective effort. On one side, vaccine developers can continue to guarantee the safety and efficacy of vaccines. On the other side, guardians, relatives and caregivers are all involved in the decision-making process for the elders via innovative communication strategies and promoting awareness campaigns to educate the public. As infectious diseases like influenza and COVID-19 threaten the health of this aging population, there is now more than ever, a need to understand how to protect them through vaccination.

About The Author

Stefania Jiang

Stefania Jiang is an Associate at Bridge Consulting. With a background in International Relations, she aspires to connect China and the world through cross-cultural communication, digital storytelling and knowledge sharing. Find Stefania on LinkedIn.