Health Equity in China: Lessons to Learn from the COVID-19 Pandemic

April 7, 2021 | By Marisa Lim, 2021 Spring Intern, Bridge Consulting

This World Health Day (April 7, 2021), the World Health Organization has called on leaders to “build a fairer, healthier world”, and to ensure that all people are able to access quality health services whenever and wherever they need them. COVID-19 has hit all countries hard, but its impact has been harshest on those communities which were already vulnerable, who are more exposed to disease, and less likely to have access to quality health care services. These unequal consequences of the pandemic have revealed the importance of health equity – the absence of unfair and avoidable or remediable differences in health among population groups defined socially, economically, demographically, or geographically.

For decades, China has strived to achieve health equity nationwide, but with a population of nearly 1.4 billion people, this has been no easy feat. While China has tackled a slew of diseases, uneven development, an ageing population, and rising expectations about health, the pandemic still tested its healthcare system and exposed deeply rooted health inequity issues. The COVID-19 pandemic thus presents China and international partners an opportunity to reflect on these issues and seek ways of improvement.

Health inequities in China exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic

While China has always strived to achieve health equity nationwide, it continues to have to reckon with deep-rooted health inequities which have been difficult to eradicate. These lapses have been worsened during the pandemic, when mass lockdowns and quarantine measures were implemented, and healthcare resources were stretched thin. These inequities include:

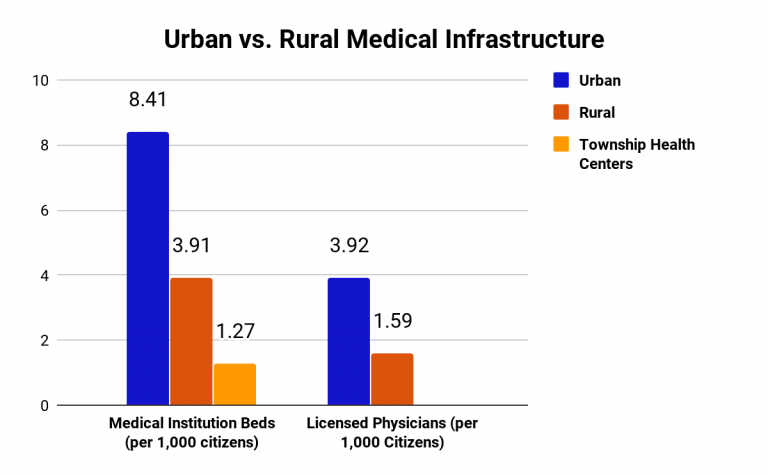

Rural health. Due to differences in socio-economic status, medical infrastructure in suburban regions of China is much less developed than those in urban regions, with less than half as many medical institution beds and licensed physicians per 1,000 citizens in rural areas compared to urban areas. Populations in rural areas not only have less access to healthcare, but also health insurance and information on the pandemic. While COVID-19 treatment was generally accessible during the pandemic, more people in rural areas had to delay their non-COVID-19 health needs due to lack of available services, compared to in urban areas.

Elderly health. With a rapidly aging population, 10% of elderly citizens in China are residents at institutions and 90% stay at home. During the pandemic, the incomes of elderly care institutions plummeted by 20%, while expenditure costs increased by 20 to 30%. This forced many institutions to cut their operations and hindered their care work. This has in turn has significantly impacted the mental health of the elderly with extended lockdowns and disruption of health services.

Non-COVID patient. In WHO global pulse survey, 90% of countries report disruptions to essential health services since COVID-19 pandemic. To reduce the risk of exposure, many public outpatient clinics, dental clinics and rehabilitation centers were closed. In China, there was a growing number of patients with urgent medical conditions unrelated to COVID-19, including liver failure, cancer and dialysis treatment, who have become collateral damage.

What has China done to address these health inequities?

In response to these dire issues, China sought several solutions to ensure equitable treatment for these affected communities. These include:

Funding construction of temporary facilities. To address the lack of medical infrastructure to support COVID-19 response measures in less developed regions, China built numerous temporary and permanent facilities. One example was the immediate construction of a 1,500-room hospital for COVID-19 patients in Nangong, Hebei, which was constructed in just five days, shortly after an outbreak in its rural areas sparked concerns among authorities due to its lack of medical facilities. These new facilities did alleviate some of the pressure on China’s healthcare system, but other issues such as shortage of experienced medical personnel and medical equipment remained.

Strengthening financial protection. For people with severe symptoms lacking health coverage, seeking medical attention was a concern due to the cost of treatment. To minimize the spread of the virus because of such patients, the National Healthcare Security Administration and Ministry of Finance immediately issued a notice to guarantee that the out-of-pocket medical expenses of all patients confirmed to have COVID-19 would be subsidized by the government, and this policy was later extended to all suspected cases. Prior to the pandemic, the government has also improved health coverage from less than 30% to almost 100% in the past decade, as part of the Healthy China 2030 plan.

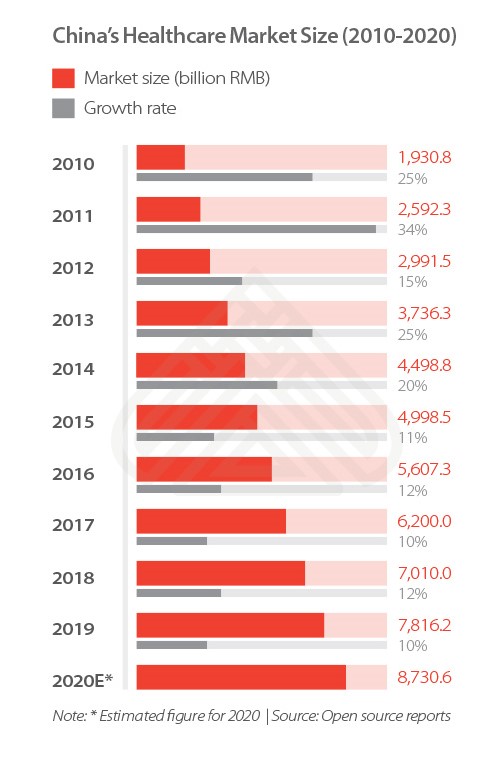

Capitalizing on digital healthcare. With many outpatient clinics closed and medical supplies low, patients with non-COVID-19 symptoms were one of the hardest hit groups during the pandemic. Digital healthcare, however, provided a promising solution to this issue. In turn, the pandemic had accelerated the development of many digital health platforms, including WeDoctor and Alibaba Health. These platforms allow online consultations between patients and healthcare professionals, and facilitate the delivery of medicine from healthcare institutions to patients. In light of the rise of digital health, there were also initiatives to encourage digital accessibility in rural regions. With these platforms, non-COVID-19 patients could still have online consultations with doctors and receive medicine deliveries despite the closure of outpatient clinics.

How can international partners help?

While China has taken major efforts to address its health inequity issues amid the pandemic, there is still more that can be done post-pandemic. International partners can contribute to China’s efforts in the following ways:

Strengthen rural healthcare through funding. While health services in China are largely maintained by the State, there are independent programs run by international organizations to provide more funding towards medical services in rural regions. Launched in 2008, the China Rural Health Project, supported by the World Bank and the Department for International Development (DfID) of the United Kingdom, was implemented in 40 counties in eight provinces within China, focusing on the rural health insurance system, health service delivery, reform of the county-level public hospitals, and capacity strengthening.

Reform current public health measures. China’s primary health care and emergency response system for infection diseases were greatly tested during the pandemic. An international partner’s perspective can provide insights into how China can better optimize its health systems. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is actively supporting China in its long-term systems change to facilitate and deepen international collaboration, and promote sustained research and development investment in public health.

Improve current healthcare system. International partners can also contribute insights from other countries to better optimize China’s overall healthcare system, including public hospitals and medical care. In 2017, the World Bank Group and the Chinese government jointly launched the China Health Reform Program-for-Results (PforR), which aims to improve the quality of healthcare services and the efficiency of the healthcare systems in Anhui and Fujian provinces, with a specific focus on comprehensive public hospital reform. The program also aims to implement a People-Centered Integrated Care (PCIC) based health system, which will benefit 107.7 million people in the two provinces over four years.

Improve current healthcare system. International partners can also contribute insights from other countries to better optimize China’s overall healthcare system, including public hospitals and medical care. In 2017, the World Bank Group and the Chinese government jointly launched the China Health Reform Program-for-Results (PforR), which aims to improve the quality of healthcare services and the efficiency of the healthcare systems in Anhui and Fujian provinces, with a specific focus on comprehensive public hospital reform. The program also aims to implement a People-Centered Integrated Care (PCIC) based health system, which will benefit 107.7 million people in the two provinces over four years.

Support research into non-COVID-19 diseases. Besides preventing the spread of COVID-19, China is also tackling a slew of non-communicable diseases that are rampant in its population, such as tuberculosis and hepatitis C. International partners can potentially improve responses to such diseases, which are a significant hindrance to China’s health equity. Find out more in our other article on how international partners can help to eliminate hepatitis C in China.

Takeaways

Over the past year, the COVID-19 pandemic has tested the healthcare systems of all countries around the world, including China. China has taken the necessary steps to address health inequities in its COVID-19 response, but the pandemic has undoubtedly aggravated many deep-rooted disparities for various communities. International partners can contribute in several ways to China’s efforts, working towards the common goal of building a fairer, healthier future for the world.

About The Author

Marisa Lim

Marisa Lim is a Singapore-based aspiring trailblazer majoring in Biomedical Engineering with a specialization in Robotics, passionate about global health and social causes. Find Marisa on LinkedIn.