China has surpassed 1 billion vaccine exports: But what more can it do?

This opinion article was originally published on China-Africa Project on October 15, 2021.

Staff members work on a joint-production line of China’s Anhui Zhifei COVID-19 vaccine at Uzbek pharma Jurabek Laboratories in Uzbekistan, on Sept. 5, 2021. (Photo by Zafar Khalilov/Xinhua)

November 15, 2021 | By Alex Henderson, Senior Associate; Zoe Leung, Junior Associate; Marisa Lim, Junior Consultant; Christine Ow, Junior Consultant, Bridge Consulting

Global demand for COVID-19 vaccines has never been of higher significance. While many countries have already reached high vaccination rates, new rationales have again increased the relevance of vaccines. In high-income countries, booster shots have become the norm, and the recent endorsements for child vaccination have produced a new target group for COVID-19 vaccines. Meanwhile, the World Health Organisation (WHO) and other concerned authorities are continuously advocating for more accessible and affordable vaccines for developing nations.

For its part, China has without a doubt, stepped up its vaccine distribution and kept true to its promise of making them a ‘global public good.’ In its ongoing efforts through both bilateral and multilateral channels, China is now the biggest COVID-19 vaccine exporter and, in doing so, has helped to minimize the gap in worldwide vaccine equity. Currently, China’s bilateral vaccine distribution stands at an impressive figure of over one billion deliveries. In addition, 28.8 million Chinese vaccines have already been delivered to recipient countries through COVAX, the global vaccine sharing system.

As we approach the two-year mark since the pandemic outbreak, it is worthwhile to evaluate how China’s overseas COVID-19 vaccine roll-out has been faring over time: its positive but sometimes controversial reception in recipient countries, its uneven but high-volume deliveries and ultimately, what might lie ahead for the future of Chinese-made COVID-19 vaccines.

China and COVAX

On 9th October 2020, China joined COVAX, marking a monumental step forward for the country’s involvement in multilateral efforts to provide vaccines to low and middle-income countries. One of the most notable but perhaps low-profile achievements over the past few months has been COVAX’s kickstart of Chinese vaccine deliveries. Although bilateral deliveries provide a greater platform for displaying brotherly relations between countries, deliveries through COVAX exemplify China’s active participation in multilateral affairs and the much-needed international validation of their vaccines, which remains a hot topic due to efficacy concerns.

The first batches of Chinese vaccines under COVAX were shipped to Pakistan and Bangladesh early in August as part of the signed Advance Purchasing Agreement with Gavi to supply 110 million doses of Sinopharm and Sinovac in Q3 and the option for purchasing 440 million more in Q4 and early 2022. However, by the end of October, the two manufacturers had only been able to provide around 30 million doses as part of their commitments to COVAX. To a broader extent, this surprisingly low number reflects the shortfalls in COVAX’s global supplies. Nonetheless, total allocations and vaccine purchases through COVAX have reached 60 million for Chinese vaccines. Some countries like Uganda, for example, have already committed to purchasing a hefty 18 million dose order of Sinopharm vaccines through COVAX.

With the international recognition of their vaccines still a significant area of concern and pending commitments to fulfill, Sinopharm and Sinovac deliveries through COVAX are expected to pick up throughout the rest of the year. Moreover, as per the agreement above for the option to supply more vaccines before mid-2022, there is the possibility that in the end, 550 million doses of Sinopharm and Sinovac will eventually be shipped globally. Of course, this will depend on several factors, such as the speed and priority at which the vaccine manufacturers provide their vaccines to the COVAX facility.

Bilateral deliveries: Stronger focus yet declining volumes

Source: Bridge Consulting

Outside of China’s involvement in COVAX, bilateral vaccine agreements are still the primary means through which China contributes its doses to countries. A quick understanding of China’s vaccine delivery trends will show a consistent focus towards Asian countries. While some countries like Indonesia still lead the way in purchases and deliveries, others like Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Iran have recently emerged to become primary recipients of Chinese vaccines.

In August, Iran had only imported slightly over 21 million doses, with over 67% coming from China – hardly enough to curb their then rapidly increasing COVID-19 death toll. Since then, the country has managed to receive tens of millions more of Sinopharm doses, with the Iran Red Crescent Society just recently announcing the completion of 33 consignments of Chinese vaccines imported from the Red Cross Society of China. Altogether these amounted to an astonishing 112 million doses, primarily delivered within just three months. Similarly, vaccine donations to other Asian countries have increased in the past months. Currently, all top 10 recipients of Chinese vaccine donations are countries in Asia.

While China has continuously emphasized its support for Africa, vaccine deliveries have peculiarly and consistently remained low, at only 7-8% of total deliveries. Opaque delivery plans remain “the number one nuisance” holding Africa back, according to WHO’s Regional Office for Africa. At the most recent 76th United Nations General Assembly, many African leaders voiced out their shared frustrations with this unsolved enigma. The WHO also noted that only a bare 15% of promised donations from rich countries, have been delivered to Africa.

IFRC Iran Delegate’s remark on the 30th consignment of vaccines from the Red Cross Society of China to Iran Red Crescent Society. Source: Twitter

On the upside, Chinese vaccine donations to the continent have expanded slightly in the past months. Several new countries such as Burundi, Guinea-Bissau, and Cote d’Ivoire recently received their first batches of Chinese vaccines. With the upcoming Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) Ministerial Meeting that will be taking place in Dakar, Senegal on 29th – 30th November, it is anticipated that new agreements and commitments for vaccine support might be announced between China and relevant African countries.

Lastly, while bilateral vaccine distributions to Asia and Africa have increased, those to Latin America and Europe have dwindled significantly. As Latin America and the Caribbean are on track to reach the WHO COVID-19 vaccination target of 40% before the end of the year, it appears that the urgent need for more vaccine supplies is not as crucial now as it was previously.

In Europe, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has not yet approved Chinese-made vaccines, hence why they are not widely used in European countries. However, national medical regulators have authorized the vaccines for emergency use, meaning some some Central and Eastern European countries such as Hungary, Serbia, and Montenegro have initiated Chinese-made vaccines as part of their vaccination drives.

Joint Production: Yet to reach maximum output

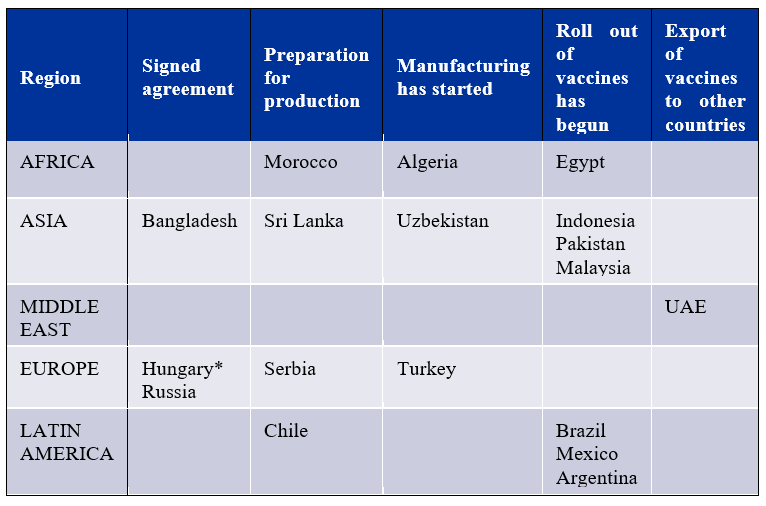

Progress of overseas joint production. Source: Bridge Consulting | *Hungary: Letter of intent signed – not a bilateral/commercial agreement

Chinese joint-vaccine manufacturers are relatively new to the global production and supply network compared to the more advanced Western vaccine manufacturers. AstraZeneca, for example, has 25 manufacturing partners across more than 15 countries. In contrast, Pfizer already has an extensive manufacturing network in the U.S and Europe, which it has activated to produce its COVID-19 vaccines. On the other hand, Chinese vaccine developers have just started establishing some of their joint production agreements in recent months. Still, with a total of 18 joint production agreements spanning four regions worldwide, not only are Chinese joint vaccine productions benefitting national vaccination campaigns, but they are also proving beneficial for regional vaccine access.

While these joint partners may have received the technology and expertise required to ‘fill and finish’ the vaccines locally, they still rely on China to supply the raw vaccine materials. Hence there is a potential that while bilateral distributions fall, supply deliveries will continue to gain ground in aiding other countries’ domestic production of Chinese vaccines. Additionally, with some countries still preparing their facilities or just starting the manufacturing, peak outputs have yet to be reached. As such, if tallying up the expected manufacturing outputs for each joint production and assuming all stated facilities are built; ideally, 1.3 billion Chinese vaccine doses will be produced each year.

Efficacy concerns remain

But it has not always been good news for Chinese COVID-19 vaccines. Skepticism over their efficacy persists as the widespread prevalence of COVID-19 variants undermine the protection given by inactivated vaccine. Regions and countries that relied heavily on Chinese vaccines have been greatly affected, often with COVID-19 case counts rising again. This has led to the increased use of non-Chinese-made vaccines as boosters on top of Chinese vaccines and a growing trend in the discontinuation of Chinese vaccines in some countries.

Of course, some studies have shown that Chinese vaccines are generally effective against deaths and severe illnesses. But others are concerned with the rapid waning of antibody counts, especially for the elderly. Most recently, studies in Brazil, Argentina, and Chile that showed low effectiveness following two doses of Chinese vaccines influenced the decision by the WHO to recommend third-dose shots to people over 60 who had received Sinovac or Sinopharm.

Moving away from Chinese vaccines

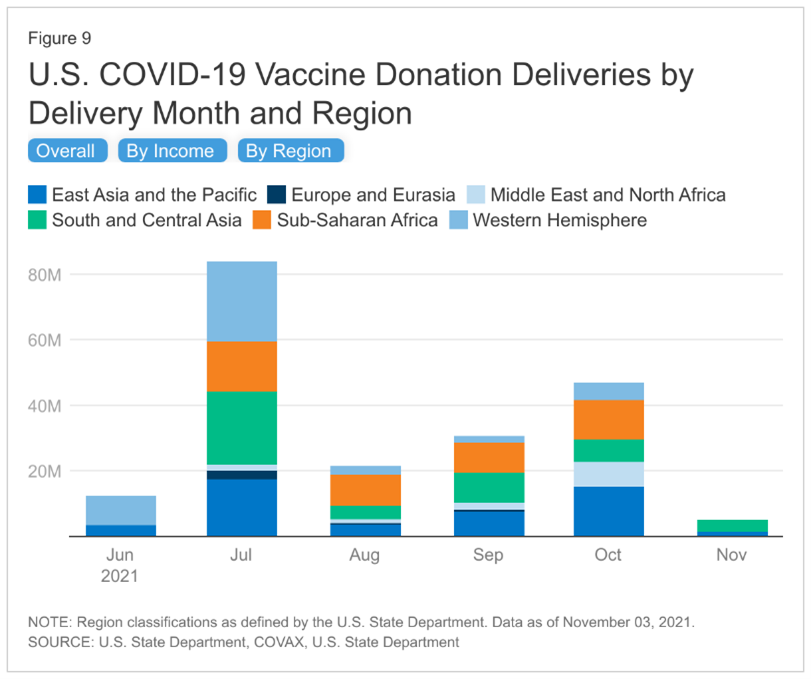

As India’s vaccine export ban starts loosening, U.S. vaccine donations start picking up again, and developing countries start having improved access to various vaccine supply channels, some countries have begun pivoting away from renewing contracts to buy Chinese vaccines.

In Brazil, Latin America’s biggest Chinese vaccine buyer and home to a joint vaccine production with Sinovac, the government has chosen not to purchase any more Chinese vaccines since September 2021. Having not been selected for use as a booster or for vaccinating children, the Sinovac’s joint production with Butantan Institute has had to look elsewhere in the region for vaccine buyers.

In Thailand, though previously having used Sinovac doses in mix-and-match regimes with Pfizer due to efficacy concerns, the country has announced that it will stop using Sinovac vaccines after current supplies run out. Instead, they have indicated that they will only “procure vaccines effective against new variants” and have already negotiated for more supplies of Astra-Zeneca vaccines.

Despite this concerning growing trend, several countries have defended the role of Chinese vaccines in acting as a ‘stopgap’ that offset global vaccination distribution delays caused by India’s vaccine export ban, COVAX’s supply shortfall, and high-income countries’ vaccine hoarding earlier on in the pandemic.

Even now, there is a demand for these vaccines. Singapore recently approved Sinovac as an alternative for those who are medically unable or unwilling to take mRNA vaccines. Other countries have begun inoculating younger age groups with China’s vaccines, indicating a certain level of trust and an inclination towards using the more familiar inactivated vaccine technology for children. To date, countries including Chile, the UAE, Argentina, Cambodia, Indonesia, Zimbabwe, and Bahrain have all approved the vaccines for use among children. As such, China’s COVID-19 vaccines may be facing a shifted target population rather than an outright rejection.

PM of Cambodia Samdach Techo Hun Sen invites campaign for the vaccination of children aged 6 to 12 years in September 2021, primarily using Sinovac vaccines (Photo from Facebook)

What’s next for China’s COVID-19 Vaccines?

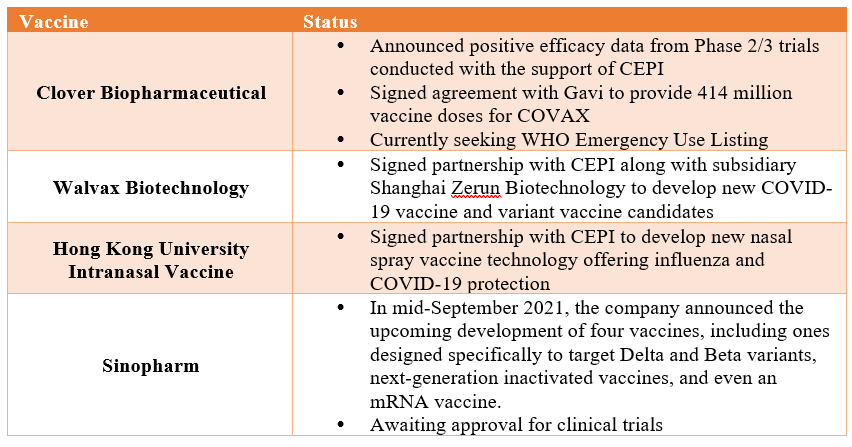

With the ongoing saga over efficacy concerns, it is noteworthy that there has been growing research and investment in China to develop next-generation vaccines that are poised to be more resilient against new variants. Mainstream companies such as Sinopharm have already stated that they have developed such vaccines to upgrade their current vaccine portfolio, while new companies such as Clover and Walvax are entering the fray to produce new Chinese-made COVID-19 vaccines.

Some of these new vaccines have already earned international support and unlike previous Chinese vaccines that primarily received state support for clinical development, are jointly developed and invested in by CEPI. This new type of cooperation will aid in ensuring the due diligence and credibility attached to their vaccine development, eliminating potential claims of lack of transparency or verifiable clinical data that previously affected past Chinese-made vaccines. In addition, some of these new companies have stated that the pandemic has taught them vital lessons on managing international trials and following scientific protocols. As Walvax’s Vice Chairman said, “We are learning from Pfizer, learning from Moderna, to do everything just as rigorously and along with the same standards.”

Source: Bridge Consulting

Moreover, as booster shots become increasingly common across countries both in homologous three-dose regimes and in mixed heterologous regimes with Western vaccines to boost immunity, there are opportunities for Chinese manufacturing companies to optimize their vaccines and booster shots to hedge against supply shocks.

Beyond COVID-19 vaccine support

Staff members unload a batch of 300,000 doses of Sinopharm COVID-19 vaccine donated by the Chinese government at Kigali International Airport in Kigali, Rwanda, Nov. 7, 2021 (Photo by Xinhua/Ji Li)

There are other areas of cooperation that China can get involved in to provide support amidst the pandemic. In many low-income countries, inadequate public health infrastructure can hinder efforts to conduct effective vaccination campaigns. This includes not having basic transport infrastructure and logistics systems, qualified medical personnel, or cold chain facilities that can store and transport vaccines.

In this regard, China can play a more prominent role in supporting countries to improve their public health infrastructure. Such support can be extended by sending Chinese medical and public health experts, sharing practical policy advice and technical assistance, encouraging Chinese companies to help enhance recipient countries’ logistics, cold chain, data tracking, analysis, and more. In the multilateral context, China can invest in organizations that focus on vaccine research against emerging variants and jointly work with global health institutions such as the WHO, CEPI, and PATH in the research and development of COVID-19 treatments.

Conclusion

China is coming up at a crossroads in its vaccine development and outreach efforts. While multilateral vaccine deliveries are slowly starting to grow through COVAX, bilateral deliveries are facing potential stagnation as countries start favoring other vaccines. With China having promised to provide 2 billion doses by the end of this year, even with the government’s reporting of 1.5 billion vaccine doses delivered already, the country will have to work extremely hard to deliver the additional 500 million doses in the next two months, taking into account that deliveries reached a peak of only 200 million doses a month in September.

Undoubtedly, China’s ambitions to make its vaccines a global public good can be called a success story. The country has produced two vaccines that the WHO has approved for Emergency Use Listing, joined COVAX and contributed both vaccines and financial support, bilaterally delivered over 1 billion vaccines to more than 100 countries, and have established joint production partnerships in all major regions of the world.

Nevertheless, China’s continued emphasis on achieving vaccine equity and access for developing countries means that it must overcome many barriers that have started to hinder its vaccine distribution. Some of it comes from lingering questions over efficacy, discontinued vaccine demand, and preference of mRNA vaccines. Faced with these obstacles, China will need to act differently to remain a preeminent leader in the fight against COVID-19. The pandemic has proven itself to be everchanging and relentless. Therefore, it is crucial that China stays one step ahead of it at all times together with the rest of the world, so that it can be a driving force to ensure that no one gets left behind.

About the Authors

Alex Henderson

Alex Henderson is a Senior Associate at Bridge. He has 8 years of experience in foreign affairs and international cooperation. He is passionate about enhancing positive relations and collaboration between stakeholders that seek to bring positive change into the world. Find Alex on LinkedIn.

Zoe Leung

Zoe Leung is a Junior Associate at Bridge. With a background in global health and international development, she understands that health is much more than just a medical matter. She is passionate about finding ways to improve health for both the individual and society. Find Zoe on Linkedin.

Marisa Lim

Marisa Lim is a Singapore-based aspiring trailblazer majoring in Biomedical Engineering with a specialization in Robotics, passionate about global health and social causes. Find Marisa on LinkedIn.

Christine Ow

Christine Ow is a Los Angeles-based Junior Associate. She is passionate about sustainable development and environmentalism and hopes to work in those fields in the future. Find Christine on LinkedIn.