Fill, finish and beyond: How Chinese vaccine developers are exporting their ambitions

March 22, 2022 | By Zoe Leung, Associate, Bridge Consulting | Image Source: AFP

Less than two years ago, President Xi Jinping announced China’s commitment to developing COVID-19 vaccines for the world. China was not only promising greater engagement in global health affairs, but it was also anticipating that its vaccine industry could step up to the enormous challenge of producing enough vaccines for the developing world, in addition to its 1.4 billion population. At that time, it seemed overly ambitious for various reasons.

While China’s high domestic vaccine consumption rates had helped its vaccine industry attain an annual production capacity of over 1 billion doses by 2019, it had only just started developing into a vaccine exporter and had received World Health Organization (WHO) prequalification for just a handful of its vaccines. Meanwhile, the United States had their promising novel mRNA technology, and India was already home to several vaccine giants whose products were already being used worldwide.

Read our take on this: Can China Deliver on Its Promise to Make the COVID-19 Vaccine a Global Public Good?

Two years on, China has made significant progress and transformed into a top exporter of COVID-19 vaccines, outpacing many developed countries and even the global sharing program known as COVAX in terms of delivery figures. In addition, deepened bilateral and multilateral cooperation have contributed to increased donations of doses to the developing world.

Joint production and tech transfer: a more sustainable answer

Despite this paramount progress, China alone has not been able to solve the vaccine equity issue that continues to plague many parts of the world. With vaccine production unequally concentrated in the hands of a small number of high-income countries and vaccine developers, inequitable access to vaccines has had dire consequences on low- and middle-income countries, affecting a range of socio-economic issues and placing a disproportionate burden on public health spending.

In addition to this, it has become increasingly clear that a system solely based on delivering vaccines to other countries is not a guarantee for equitable vaccine immunization. Instead, capacity-building is often more critical, namely joint production knowledge and technology transfer.

It is important to note that in entering joint COVID-19 vaccine production with other countries, Chinese manufacturers have: 1) helped developing countries independently produce vaccines 2) removed the need for reliance on imports, and 3) leveraged opportunities for such countries to become a vaccine supplier for the developing world.

An existing problem: reducing reliance on imports

Many countries have sought out partnerships with China’s vaccine developers. Receiving support in the mass manufacturing of vaccines as they strive to increase resilience against external conditions that hinder vaccine supplies – critical in times of pandemics.

Without a doubt, top political directives have been a major driving force for Chinese developers’ cooperation. From the start of the pandemic, President Xi Jinping had championed the global export of Chinese vaccines and continues to advocate for China’s increased activity in this domain.

Within this larger effort, during the 8th Ministerial Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in November 2021, he emphasized on the role of joint production between Chinese companies and African countries. Previously, a 2019 Vaccine Administrative Law also encouraged local vaccine manufacturers to produce and export vaccines for international procurement, expanding out from the domestic-centered, competitive Chinese vaccine market. Joint production has thus been one way for Chinese manufacturers to distribute their products abroad.

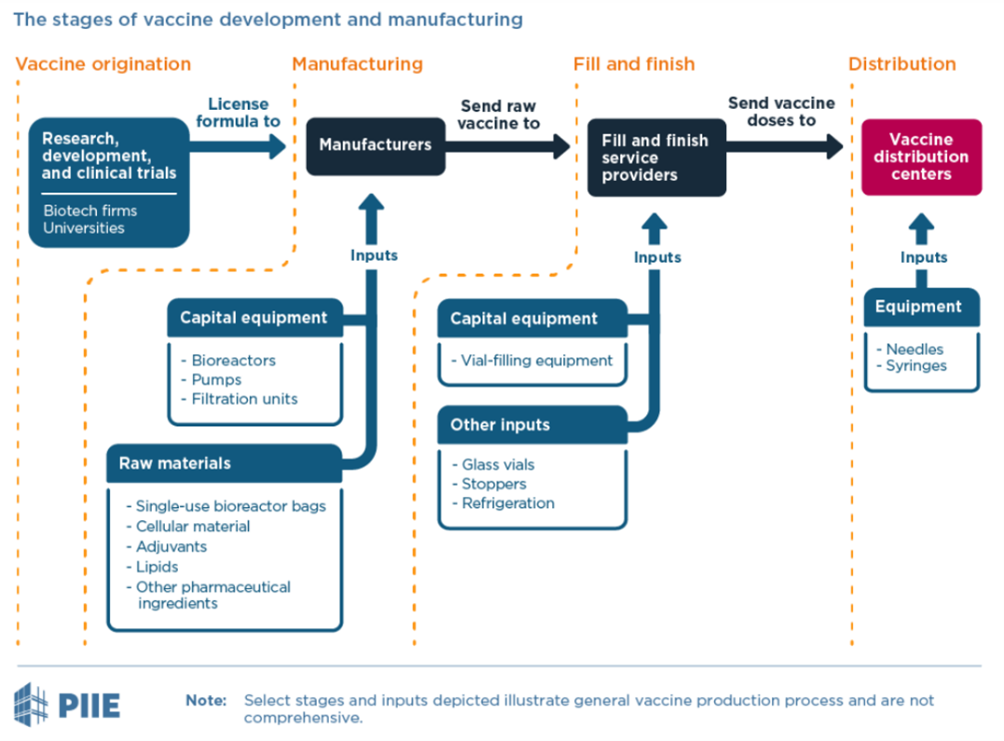

In particular, tech transfer – defined as a set of “activities that involve a capacity-building component at the recipient site intended to enable the recipient to produce a vaccine” – has enabled China to support countries’ self-sufficiency in manufacturing vaccines. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries were eager to have a stable source of vaccine supply, especially considering India’s vaccine export ban early in March 2021 that prioritized domestic vaccination over supplies for the COVAX facility. To rapidly achieve this, most of all tech transfers have been limited to the fill-and-finish stage of vaccine production, where vaccines can be packaged and finished using raw material imported from supplying countries.

Sinopharm in UAE: Hayat-Vax boosting immediate vaccine supply

UAE participated in Phase III clinical trials for Sinopharm’s vaccine in late 2020 that helped them procure millions of doses. While shipments were delayed initially due to China’s scale-up difficulties, by March 2021 the UAE was starting production of the vaccines under a joint venture between Sinopharm’s CNBG and G42, a leading tech company in Abu Dhabi. The locally produced ‘Hayat-Vax’ became a key part of the national vaccination campaign, and UAE was able to expand on their collaboration, later authorizing and producing Sinopharm’s new recombinant protein vaccines as booster shots.

Joint production can also address existing problems with local infrastructure and delivery systems that impede on immunization activities. By localizing production, manufacturing timelines can be adjusted to immediate needs, and logistics chains can be established more effectively.

See our article: Robust public health infrastructure essential for vaccine equity

Sinovac-VACSERA: a cold storage facility for regional exports

In September 2021, Sinovac’s local partner in Egypt, government-funded VACSERA announced their intention to produce a staggering 1 billion doses annually for regional exports, on top of 200 million doses for domestic immunization through joint production. For this, a new USD 33 million complex is in construction, and over 30 million doses have been produced from shipped raw materials. Further discussions have taken place over the transfer of Sinovac’s manufacturing technology, training of local staff, production of variant-specific vaccines, and possible production of vaccines for polio and influenza.

Notably, to reduce logistical barriers impeding vaccine rollout, Sinovac has indicated that it is planning to construct an automated cold storage facility within VACSERA’s complex. With the Egyptian government and VACSERA providing the land, building and necessary licenses, Sinovac will provide interior-finishing and equipment. Housing up to 150 million doses, it will be the largest such storage in Africa, able to facilitate regional vaccine exports for years to come.

While joint production has shown to address existing vaccine supply and distribution problems, in the larger context, we can also see how Chinese companies seek to leverage these joint productions to enter developing markets as an emerging vaccine supplier for the world.

An unmet need: public-private partnerships for developing countries.

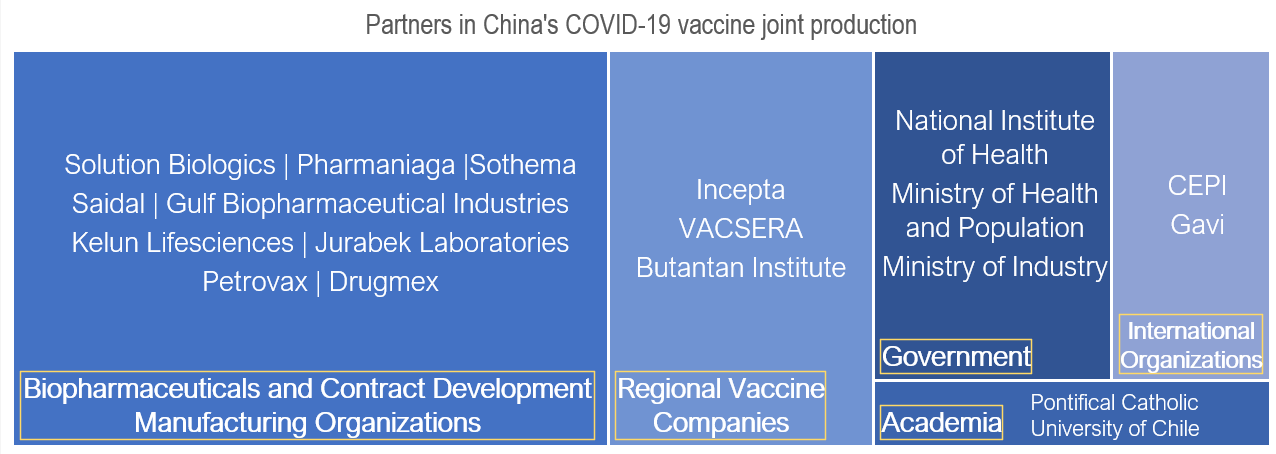

Currently, China’s existing joint production partnerships have mostly been bilateral, involving Chinese vaccine manufacturers, the recipient country’s government, and local vaccine manufacturer. These public-private partnerships have been crucial for the forward-thinking direction of the partnerships and as a source for funding in vaccine research and development, and distribution.

While high-income countries may represent a more profitable opportunity for many private vaccine developers, there is still a substantial unmet need in developing countries against existing diseases and emerging pathogens. While technical challenges and costs to tech transfers in developing countries may also be greater, public funding mechanisms have helped as incentives for companies to enter developing markets.

In doing so, the pandemic has opened additional funding and support channels from governments and international organizations wanting to leverage interest from vaccine companies to invest in vaccine distribution and technologies. Several Chinese companies have benefited from such support:

- Sinopharm and Sinovac’s vaccines received WHO Emergency Use Listing in May and June 2021, qualifying them to be procured by international organizations.

- Sinopharm, Sinovac, and Clover Biopharmaceuticals signed advanced purchase agreements with the Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, for the use of their vaccines within the COVAX Facility.

- Shanghai Zerun Biotechnology, Walvax Biotechnology, and Clover received funding from the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) for support in the development, studies, clinical trials, and scale-up to manufacturing of their vaccine candidates.

- Ecuador, Serbia, and Egypt’s governments have all provided land or buildings for Chinese construction of new vaccine research or manufacturing facilities.

Collectively, the four major Chinese COVID-19 vaccine developers – Sinovac, Sinopharm, CanSino, and Zhifei Longcom – have engaged in 22 joint production agreements with various countries.

In different ways, Chinese manufacturers have taken hold of these opportunities to engage in vaccine development, manufacturing, and tech transfer with a range of partners. Ultimately, ensuring their vaccines’ distribution to overseas populations will be guaranteed.

Sinovac in Chile: public-private-academic partnership to revitalize local vaccine production

Prior to the pandemic, Sinovac had already conducted respiratory virus vaccine research with the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. This encouraged them to establish a Sinovac Chile branch, and later enter a public-private-academic partnership to set up a new vaccine production plant in Chile and advance long-term vaccine R&D cooperation. This agreement has been welcomed greatly by the government, which anticipates a revival in Chile’s local vaccine production capacity.

With an investment of USD 100 million, Sinovac procured an 11,000 square meter facility in late January 2022. It will house the fill-and-finish production line expected to begin making 50 million doses of COVID-19, hepatitis A and influenza vaccines by the end of 2022.

The University has also provided research space for Sinovac Chile’s team within their facilities, and the Ministry of National Assets has released a piece of land for them to construct a new research center. In the long-term, Sinovac has also discussed cooperation with local universities to provide diploma and master’s courses for professionals interested in producing, monitoring and selling vaccines.

While Sinopharm and Sinovac have achieved the most success, their inactivated vaccines are not the only driver of Chinese vaccine outreach. CanSino and Zhifei Longcom’s vaccine, both developed through research collaborations with Chinese academicians, have also facilitated partnerships that allow them to be an asset both domestically and abroad.

CanSino’s steady progress

The one-dose adenoviral vector vaccine by CanSino was created in collaboration with academician Chen Wei of the Academy of Military Medical Sciences, who had previously played a hand in developing their approved Ebola vaccine. CanSino primarily partnered with Pakistan and Mexico to undergo fill-finish processes. In Pakistan, the National Institute of Health received production technology for the fill-and-finish, training on quality control, and was able to roll out their locally-branded “PakVac” in national programs by June 2021.

While beleaguered for not yet receiving international recognition, CanSino has remained steady in its progress to further innovate its technology. In December 2021, it partnered with Irish medical device company Aerogen to develop an inhaled version of their vaccine, which is currently in promising late-stage clinical trials. Domestically, while it was at first only administered for select populations due to limited manufacturing capacity, in Feb 2022, the State Council authorized its use as a ‘mixed’ sequential booster for inactivated vaccines, driving up demand for the vaccine.

Zhifei Longcom: success in Uzbekistan

Zhifei Longcom partnered with Chinese Academy of Science’s Institute of Microbiology, led by academician George Gao (Director-General of China CDC) to develop their adjuvanted protein subunit vaccine.

Their vaccine was first authorized in Uzbekistan thanks to the country’s participation in a Phase III trial, and the company later signed a joint venture agreement with local Jurabek Laboratories to fill-and-finish the vaccines. Jurabek has continuously produced the vaccines since October 2021, amounting to 38 million doses delivered and locally filled, used in the national immunization campaign. Like CanSino, it recently received greater domestic attention as a sequential booster, showing its capability to be used both overseas and domestically.

Consequentially, developing COVID-19 vaccines, engaging in exports and overseas production have meant a significant revenue boost for companies. In the first half of 2021, Sinovac reported sales revenue of USD 11 billion, a 160-fold increase compared to 2020. CanSino reported a turnaround from net loss to profit in 2021, mainly attributed to the commercialization of their COVID-19 vaccine, with future prospects placed on their aerosol vaccine. Zhifei Longcom, meanwhile, reported a net profit of CNY 3.45 billion in the first half of 2021, attributed vastly to sales of their COVID-19 vaccine. Of course, Sinovac has acknowledged the temporariness of this trend, that even with revenue from the sale of booster shots, the dwindling of the pandemic and competitiveness from other vaccines would reduce sales in the long term.

What do Chinese vaccine developers gain from joint production and tech transfer?

Ultimately in moving to joint productions, Chinese vaccine developers can expand their overseas business more sustainably while fulfilling China’s global advocacy for vaccine equity.

In the short-term, they can expand their consumer base for COVID-19 vaccines through involvement in fill-and-finish partnerships and construction of vaccine manufacturing plants; supply the vaccines for national or even regional vaccination campaigns. In the long-term, they can seek to leverage their partnerships to conduct research, develop and/or produce vaccines for polio, hepatitis, influenza, and even unknown pathogens, known as “Disease X”.

These partnerships are the type that embraces the idea of capacity-building rather than vaccine aid, addressing current supply imbalances while benefitting the local and regional ecosystems of vaccine manufacturing and delivery to provide vaccines as a true global public good.

About The Author

Zoe Leung

Zoe Leung is an Associate at Bridge. With a background in global health and international development, she understands that health is much more than just a medical matter. She is passionate about finding ways to improve health for both the individual and society. Find Zoe on Linkedin.